'Game Changers' Celebrates Pioneers Of Women's Track And Field

'Game Changers' Celebrates Pioneers Of Women's Track And Field

Molly Schiot's book "Game Changers: The Unsung Heroines of Sports History" celebrates the female trailblazers who paved the way for women in sports.

Before women won Olympic gold medals, before they broke world records, and before they were even allowed to compete in athletics, there were a brave few who dared to be the first.

Based on the Instagram account @TheUnsungHeroines created by filmmaker Molly Schiot, "Game Changers" is a recently released book that celebrates 150 female athletes who broke barriers and paved the way for women in sports in the pre-Title IX era. The stories of game-changers on and off the field are told with the hope of giving "these foremothers the attention and recognition they deserve."

Schiot detailed the stories of several track and field pioneers, notably Kathrine Switzer, Betty Robinson, Alice Coachman, Earlene Brown, Nawal El Moutawakel, Louise Stokes and Tidye Pickett, Zola Budd, Stella Walsh, Wilma Rudolf, and many more. Women's track and field owes much of its success to the bravery and groundbreaking accomplishments of these game-changers.

Kathrine Switzer

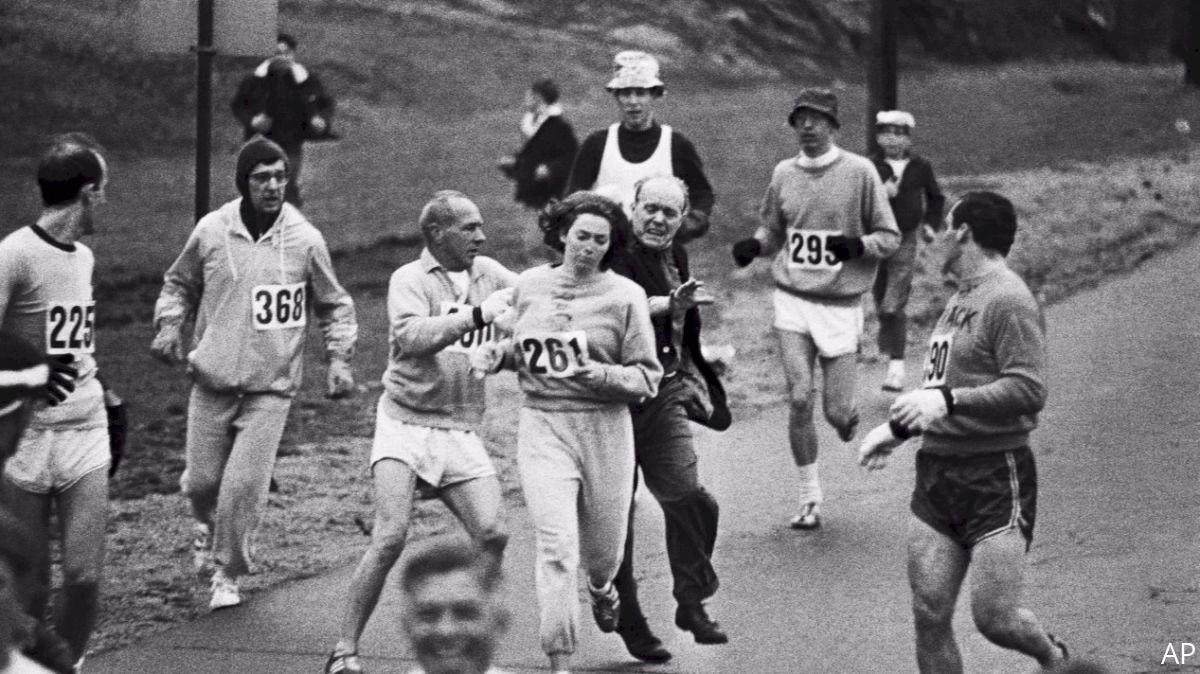

In a time when the Boston Marathon only welcomed male runners, Kathrine Switzer became the first female to register and complete the race. Although there was no specific rule that barred women from competing at the 1967 Boston Marathon, 740 runners in the race were men with the exception of Switzer, who registered under the gender neutral signature "K.V." Boston Athletic Association officials didn't notice any irregularities, and Switzer was given bib number 261 as a registered participant. She ran with her Syracuse cross country coach, Arnie Briggs, and boyfriend, Tom Miller, who helped pace her through the 26.2 miles. The initial response from the crowd was positive--cheers, thumbs up, and high fives were given as fans quickly noticed Switzer as the only female runner in the field. The cheers subsided when co-race director Jock Semple famously tried to push her off the course, only to be stopped by Miller.

"Get the hell out of my race, and give me those numbers! What are you trying to prove? When are you gonna quit?" Semple screamed at Switzer.

In a later interview, Switzer recalled thinking: "I'm gonna finish this race on my hands and knees if I have to...because nobody thinks I can do this. ... If I don't finish this race, then everybody's going to believe women can't do it, and that they don't deserve to be here, and that they're incapable. ... I've got to finish this race."

She finished in 4:20 as the first woman to register and complete the Boston Marathon. Five years later, in 1972, women were finally allowed to compete. In 2016, 14,112 women competed in the Boston Marathon. Since Switzer's historic run in 1967, many women have enjoyed the opportunity to not only participate, but also make a career out of professional marathon running.

"I met her when I ran Boston the first time in 2009," two-time Olympian Kara Goucher told espnW in 2012. "It is fair to say that her courage to run the Boston Marathon paved the way for me to live the life that I do. Thanks to her bravery, I am living my dreams and running professionally."

Betty Robinson

In 1925, Betty Robinson was running to catch a train in her hometown of Harvey, Illinois, when her biology teacher noticed her speed against the train. Legend has it that Robinson outran the train. In shock and awe, Robinson's teacher challenged her to run a 50-yard dash inside the hallway of her school. From that point on, Robinson began competing in track meets. In three short years, she became the United States' hope for glory at the 1928 Olympic Games in Amsterdam--the first Olympics which allowed female track and field athletes to compete. At 16 years old, Robinson became the first woman in history to win a gold medal at the Olympic Games. Because the 100m race was the first of five women's track events at the 1928 Games, Robinson won the first gold medal handed out in women's track and field. The accomplishment was one of many in a series of unbelievable feats that highlight Robinson's life.

In 1931, Robinson and her cousin were flying in a biplane when the engine stalled and caused the plane to crash near the Chicago area. According to reports, Robinson was believed to be dead when her body was pulled from the debris. She was even taken to an undertaker, where it was discovered that she had survived the crash. She was hospitalized for 11 weeks, and doctors tended to her head injuries, a broken leg, and arm. They placed a silver rod and pin inside her leg, and she was forced to remain in a hip-to-heel cast for months, during which time her leg became a half-inch shorter. Robinson didn't return to the track for three and a half years.

"Of course I am going to try and run again," Robinson told reporters. "After spending the last eight years in preparation for an athletic career, it would be useless for me to give up without at least an attempt to run."

When she returned, she couldn't bend her knee for a crouched start, which left the open 100m out of the question. However, Robinson discovered that she could contribute to the relay team from a standing start. Miraculously, she made the 1936 Olympic team headed to Berlin. While running the third leg, Robinson helped Team USA capture the gold against the record-setting German squad, which dropped the baton on the final handoff. The performance marked her second gold medal of her career and an unbelievable comeback from a near-death experience. However, her story became overshadowed by Jesse Owens' legendary performance against Adolf Hitler's claims of Aryan supremacy.

By the time Robinson retired, she held world records in the 50, 60, 70, and 100 yards. She was later inducted into the United States Track and Field Hall of Fame. In 2014, sportswriter Joe Gergen published a book based on Robinson's life, "The First Lady of Olympic Track: The Life and Times of Betty Robinson."

"I find it astonishing she's not even in the Olympic Hall of Fame," sportswriter Joe Gergen told the Chicago Tribune. "She should have been one of the first people put in, but she's not there."

Learn more stories of the "Unsung Heroines" of track and many more sports by reading "Game Changers."

Based on the Instagram account @TheUnsungHeroines created by filmmaker Molly Schiot, "Game Changers" is a recently released book that celebrates 150 female athletes who broke barriers and paved the way for women in sports in the pre-Title IX era. The stories of game-changers on and off the field are told with the hope of giving "these foremothers the attention and recognition they deserve."

Schiot detailed the stories of several track and field pioneers, notably Kathrine Switzer, Betty Robinson, Alice Coachman, Earlene Brown, Nawal El Moutawakel, Louise Stokes and Tidye Pickett, Zola Budd, Stella Walsh, Wilma Rudolf, and many more. Women's track and field owes much of its success to the bravery and groundbreaking accomplishments of these game-changers.

Kathrine Switzer

In a time when the Boston Marathon only welcomed male runners, Kathrine Switzer became the first female to register and complete the race. Although there was no specific rule that barred women from competing at the 1967 Boston Marathon, 740 runners in the race were men with the exception of Switzer, who registered under the gender neutral signature "K.V." Boston Athletic Association officials didn't notice any irregularities, and Switzer was given bib number 261 as a registered participant. She ran with her Syracuse cross country coach, Arnie Briggs, and boyfriend, Tom Miller, who helped pace her through the 26.2 miles. The initial response from the crowd was positive--cheers, thumbs up, and high fives were given as fans quickly noticed Switzer as the only female runner in the field. The cheers subsided when co-race director Jock Semple famously tried to push her off the course, only to be stopped by Miller.

"Get the hell out of my race, and give me those numbers! What are you trying to prove? When are you gonna quit?" Semple screamed at Switzer.

In a later interview, Switzer recalled thinking: "I'm gonna finish this race on my hands and knees if I have to...because nobody thinks I can do this. ... If I don't finish this race, then everybody's going to believe women can't do it, and that they don't deserve to be here, and that they're incapable. ... I've got to finish this race."

She finished in 4:20 as the first woman to register and complete the Boston Marathon. Five years later, in 1972, women were finally allowed to compete. In 2016, 14,112 women competed in the Boston Marathon. Since Switzer's historic run in 1967, many women have enjoyed the opportunity to not only participate, but also make a career out of professional marathon running.

"I met her when I ran Boston the first time in 2009," two-time Olympian Kara Goucher told espnW in 2012. "It is fair to say that her courage to run the Boston Marathon paved the way for me to live the life that I do. Thanks to her bravery, I am living my dreams and running professionally."

Betty Robinson

In 1925, Betty Robinson was running to catch a train in her hometown of Harvey, Illinois, when her biology teacher noticed her speed against the train. Legend has it that Robinson outran the train. In shock and awe, Robinson's teacher challenged her to run a 50-yard dash inside the hallway of her school. From that point on, Robinson began competing in track meets. In three short years, she became the United States' hope for glory at the 1928 Olympic Games in Amsterdam--the first Olympics which allowed female track and field athletes to compete. At 16 years old, Robinson became the first woman in history to win a gold medal at the Olympic Games. Because the 100m race was the first of five women's track events at the 1928 Games, Robinson won the first gold medal handed out in women's track and field. The accomplishment was one of many in a series of unbelievable feats that highlight Robinson's life.

In 1931, Robinson and her cousin were flying in a biplane when the engine stalled and caused the plane to crash near the Chicago area. According to reports, Robinson was believed to be dead when her body was pulled from the debris. She was even taken to an undertaker, where it was discovered that she had survived the crash. She was hospitalized for 11 weeks, and doctors tended to her head injuries, a broken leg, and arm. They placed a silver rod and pin inside her leg, and she was forced to remain in a hip-to-heel cast for months, during which time her leg became a half-inch shorter. Robinson didn't return to the track for three and a half years.

"Of course I am going to try and run again," Robinson told reporters. "After spending the last eight years in preparation for an athletic career, it would be useless for me to give up without at least an attempt to run."

When she returned, she couldn't bend her knee for a crouched start, which left the open 100m out of the question. However, Robinson discovered that she could contribute to the relay team from a standing start. Miraculously, she made the 1936 Olympic team headed to Berlin. While running the third leg, Robinson helped Team USA capture the gold against the record-setting German squad, which dropped the baton on the final handoff. The performance marked her second gold medal of her career and an unbelievable comeback from a near-death experience. However, her story became overshadowed by Jesse Owens' legendary performance against Adolf Hitler's claims of Aryan supremacy.

By the time Robinson retired, she held world records in the 50, 60, 70, and 100 yards. She was later inducted into the United States Track and Field Hall of Fame. In 2014, sportswriter Joe Gergen published a book based on Robinson's life, "The First Lady of Olympic Track: The Life and Times of Betty Robinson."

"I find it astonishing she's not even in the Olympic Hall of Fame," sportswriter Joe Gergen told the Chicago Tribune. "She should have been one of the first people put in, but she's not there."

Learn more stories of the "Unsung Heroines" of track and many more sports by reading "Game Changers."

Related Content

Rai Benjamin, Athing Mu And Sydney McLaughlin-Levrone Headline Mt. SAC

Rai Benjamin, Athing Mu And Sydney McLaughlin-Levrone Headline Mt. SACApr 19, 2024

Diamond League Xiamen 2024 To Include USA Track Star Sha'Carri Richardson

Diamond League Xiamen 2024 To Include USA Track Star Sha'Carri RichardsonApr 19, 2024

Marathon Master's World Record-Holder Kenenisa Bekele Excited For Return To London Marathon

Marathon Master's World Record-Holder Kenenisa Bekele Excited For Return To London MarathonApr 19, 2024

Tamirat Tola Is Confident In His Training Heading Into London Marathon

Tamirat Tola Is Confident In His Training Heading Into London MarathonApr 19, 2024

Leul Gebresilase Prepared For 2024 TCS London Marathon

Leul Gebresilase Prepared For 2024 TCS London MarathonApr 19, 2024

Mic'd Up With Ritz At The TEN

Mic'd Up With Ritz At The TENApr 19, 2024

FloSports Recognized Globally By International Sports Press Association

FloSports Recognized Globally By International Sports Press AssociationApr 18, 2024

How To Watch The Diamond League Xiamen 2024

How To Watch The Diamond League Xiamen 2024Apr 18, 2024

Diamond League Xiamen 2024 Schedule: What To Know

Diamond League Xiamen 2024 Schedule: What To KnowApr 18, 2024