Outdoor Track and Field on Flotrack 2013Apr 9, 2013 by Garrett Reim

The Fundamentals of Running with Vigilante and Salazar

The Fundamentals of Running with Vigilante and Salazar

Garrett Reim is a '10 graduate of Pepperdine University who has a passion for the physiology of running. Reim is one of our main Flotrack contributors on the west coast who's helped out at the Mt. SAC Invitational, Arcadia Invitational, the Oxy High Performance Invitational, and more. He drafted this article back back in early April so even though it has some March Madness references, we liked them so much, we kept them. If you're interested in becoming a Flotrack contributor or just have a topic that you want to write about, email us!

Fundamentals of Running

We are past March Madness and one thing is quite clear: All of the final teams had excellent fundamentals. Perhaps that is too obvious, given how important dribbling, passing, shooting, and rebounding are to basketball, but the point should not be lost on us - excellent fundamentals make excellent athletes. Such is the same for running.

However, while poor rebounding and missed shots are clear failures to master the fundamentals of basketball- you can see the error right in front of you- the fundamentals of running are not obvious. These fundamentals are subtle because they are the principles of exercise physiology. These four main principles are overload, specificity, individuality and regression.

Overload

We all know exercising the body harder than normal will make it stronger. In exercise physiology terms this is called overload.

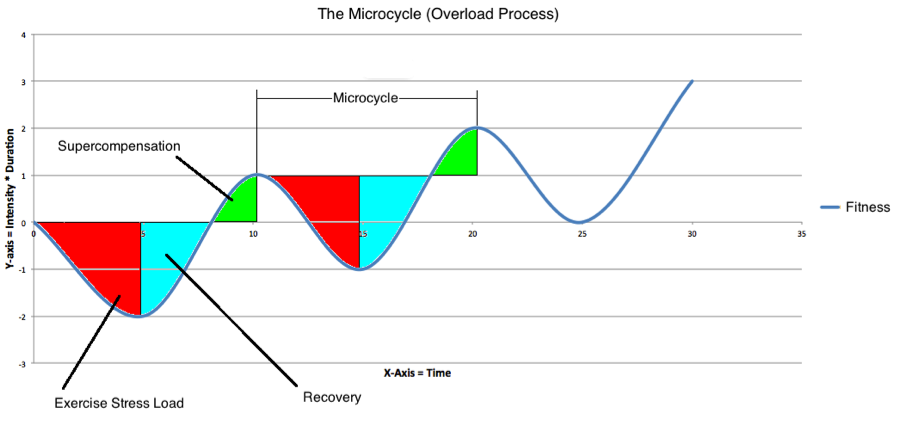

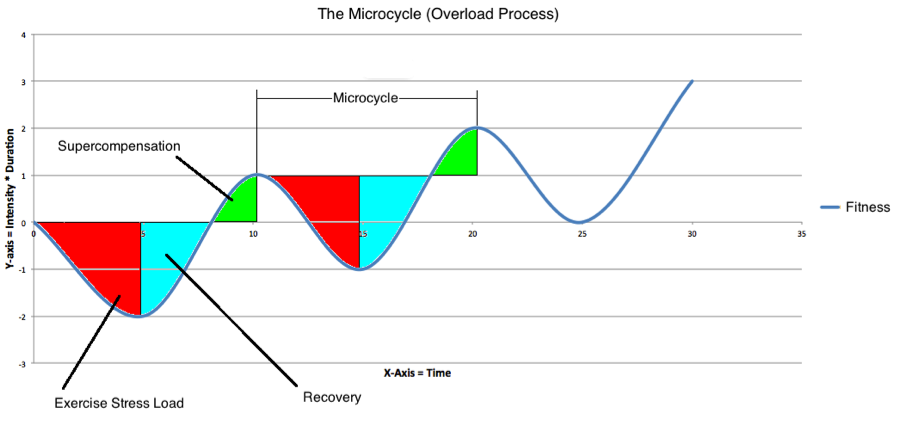

This happens in three parts: First exercise, next recovery and finally supercompensation. After recovering to a baseline of fitness, if allowed additional rest time, the body will go onto supercompensate (develop additional strength), which is the body’s natural way of being to prepare to function more efficiently next time. The below graph shows how the body is loaded with stress, recovers, then goes on to supercompensate:¨

In theory, the most efficient way of building fitness relies on balancing workouts against rest and supercompensation, then fitting as many of these cycles into a season as possible. However, in reality, finding that balance can be incredibly difficult.

The body does not give clear signs when it has fully recovered or reached peak supercompensation. Often times, we are left guessing. Combine that guessing with an athlete’s ambition to quickly improve and you have a recipe for disaster.

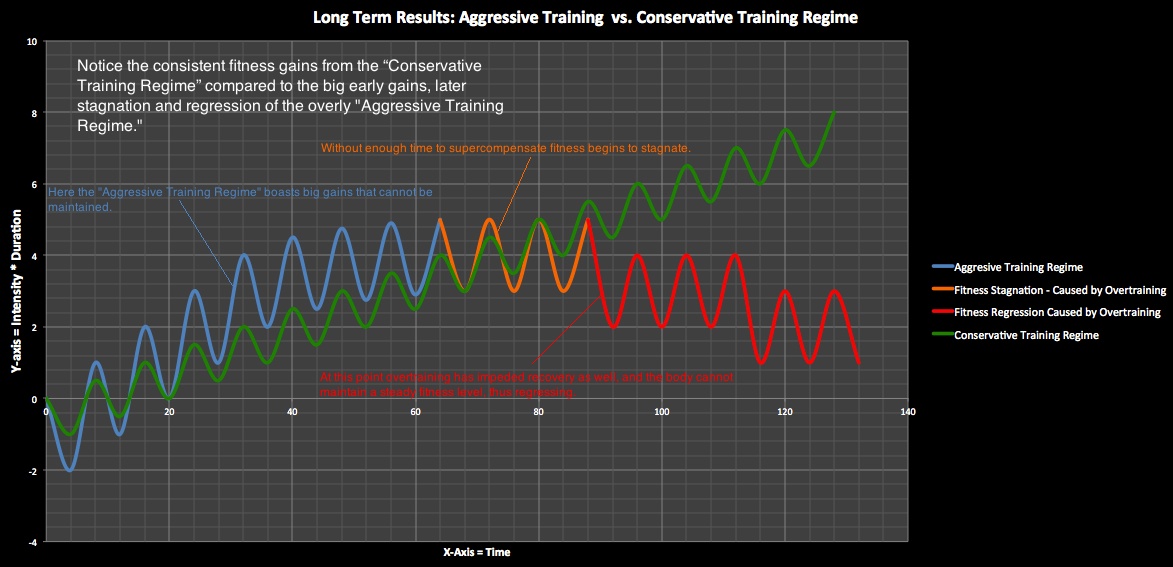

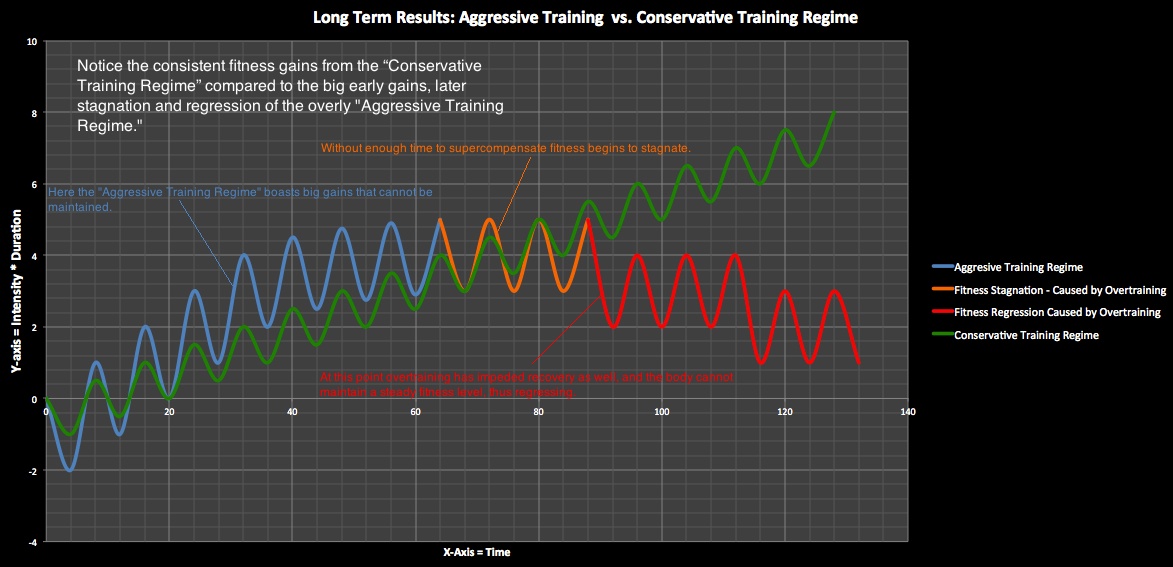

The problem is caused when an athlete trains again before recovery and supercompensation are complete. This interrupts the overload process, and stagnates their development. This is overtraining 101: Stressing the body again before it has the chance to recover and supercompensate.

So what is the best way to maximize long-term training gains without the impediment of overtraining and injury? It can be tricky to find that perfect point of training balance but some of the best coaches are honing it by taking a more conservative approach. Princeton Head Cross Country and Track Distance Coach Jason Vigilante explains this approach. “I’d rather train everyday at 75% than 4 days in a row at 110%," Vigilante said. "Doing just one more [isn't] always productive.”

Instead of risking overtraining and injury, these coaches deliberately undertrain knowing that they can get bigger returns over the long-term when their athlete’s development does not suffer interruptions from injury and overtraining.

Vigilante goes on to say, “You're not going to take a 4:20 miler to 3:59 overnight… You have to allow them to adapt.”

Some coaches insist on breaking down the athlete through exhausting training. Vigilante says, “I don’t like the tear down process. I just like to be really patient. After a couple of years, they become a successful athlete.” By taking a slightly more conservative approach Vigilante is giving up fast returns but increasing his chances of better long-term development.

Then there's the actual science. The below chart demonstrates stress, rest, and supercompensation at a more conservative pace. Notice by avoiding overtraining, the athlete gets better long-term results. See below:

Specificity

Specificity means specific exercise will bring about specific results (adaptations). Aerobic training will make you more aerobically fit and anaerobic training will make you more anaerobically fit.

This principle is obvious enough, but we often forget to what extent this principle holds true and focus too much on the aerobic benefits of slow jogging; neglecting training at race pace and becoming an athlete that is really good at running a lot (see: jogging).

What’s more, specificity also has strategic significance. Recently, Flotrack spoke with coach Alberto Salazar about his star athlete Galen Rupp. While Rupp is known for training 100+ miles per week, his coach Alberto Salazar makes sure some of his running is focused on sprinting. Rupp routinely includes 400m sprints in his training so that he has the anaerobic power to kick down the competition in the last lap of the 10,000m (see: silver medal from the 2012 London Olympics).

Galen Rupp Workout: All About the Last Lap

“If you’re never running faster than 52 in workouts, then how are you going to run 52 when you are dead tired and you’ve already run 24 laps - it doesn’t make any sense.” – Alberto Salazar

Lastly, specificity also refers to the mode of exercise - The mechanics of the overload. Are you swimming, biking or running? All three can be done aerobically but exercise physiology tells us practicing one mode of exercise has little transferable benefit for the others. Though certain muscles, for example the quadriceps muscles, are active in all three disciplines of swimming, biking and running. They are called upon to perform differently, thus the adaptations and fitness gains will be different.

Salazar keeps with the principle by emphasizing alternative aerobic exercise that closely mimics normal running, like running on the Alter-G and underwater treadmills. Both pieces of equipment lighten the impact of running on the body while still maintaining the biomechanical specificity of running.

Alter-G Treadmill - Alberto Salazar Testimonial

(Full disclosure: This is an infomercial for the manufacturer, but it is still informative)

Underwater Treadmill workout video

(Full disclosure: This is also an infomercial for the manufacturer, but it is still informative)

Athletes with fewer resources can diminish the impact of running by exercising on grass, dirt and woodchips, which are all surfaces that significantly reduce the jarring of running.

Mode specificity is reason enough to stay healthy and stay running because the best way to get better at running is running.

Individuality

Each athlete will adapt differently to the training or the principle of individuality. This is largely a genetic phenomenon, though some individual adaptations are subject to the fitness an athlete has already developed. Individuality states, "The training that returns the best result is training that is tailored to an athlete’s individual strengths."

In a team environment, this is often difficult to achieve. Coach Vigilante elaborates on the difficulty of individual training plans by saying, "To some extent you can look at each undeveloped athlete 'as a seed.' All seeds early on look similar and 'all want to grow and be great,' but you can’t always tell what their makeup is by just looking at them" Vigilante continues, “you don’t know what a kid’s upbringing was, what their foot speed is, their body composition, or personality; there is such an array of differences.”

One athlete in particular that stands out is Princeton middle-distance runner Peter Callahan. Anchor for the recent NCAA Indoor National Championship DMR team and 3:58.76 miler, coach Vigilante says Callahan hasn’t ran more than 25 miles/week this season. Though his mileage might be considered low compared to other athletes, Vigilante goes on to emphasize, “I shouldn’t expect there is consistency between athletes. Each kid has a different set of tools.” It is up to the coach and athlete to make the most of those individual differences.

Regression

The last principle of exercise physiology, regression, is the most depressing.

When an athlete ends regular exercise, fitness is rapidly lost. In one extreme example, a study showed when “subjects were confined to bed for 20 consecutive days [their] V02 max decreased by 25%.” Because of the regression principle, without regular exercise adaptions will quickly erode.

Maintenance – The Sweet Spot

While the regression principle might leave you feeling discouraged, it does come with a caveat: fitness can be maintained if an athlete keeps up some limited training. As long as an athlete maintains the same intensity in their training, they can reduce the frequency and duration of training significantly. This is tapering.

In a taper period, runners are consolidating all potential adaptations and are conceding that they will perform better by resting in the final days before a race than trying to create more adaptations.

The limits of maintenance below:

How often you run (frequency) can be reduced by 2/3, so long as intensity is maintained.

How long you run (duration) can be reduced by 2/3, so long as intensity is maintained.

How hard you run (intensity) must be maintained or fitness gains will reverse.

Honing your ability to maintenance fitness during the taper period will leave you well rested and prepared to give your best possible effort at race day.

Where Exercise Physiology Won’t Take You

For all the science that makes up the fundamentals of training, the sport is also part art. Coach Vigilante states, “You can’t overrule the fundamentals of exercise physiology.” He added, “The fundamentals are art and science.”

He goes on to say, "If I were a genius, [if] I was doing everything correct, and [if] everything was precise, you still haven’t accounted for faith, will, desire; the things that make a champion. There has to be a symbiotic relationship... the art completes a combination of the two.”

Coach Vigilante elaborates, “Some people have been conditioned that winning is everything” and “some people are gentle, so they demur at crunch time. You have to put pressure on some people and take pressure off others.” It’s important to know “what’s going to motivate this kid.”

But at the end of the day, it’s not going to be your success. Sometimes we want success more than our athletes, [but], I can’t do it for you."

Here’s where running becomes more of an art. “Sometimes we need a hug around the head or a kick in the ass,” says Vigilante.

Some athletes need to be given stern instruction and for others you need to let them learn on their own. Explaining how he provides direction to his most ambitious athletes Vigilante concedes, “You can talk to the super motivated Type A personality until you’re blue in the face.” However, “Often you can only communicate via failure.” When the athlete says “Gosh, I’m not succeeding,” that is when a coach’s direction is most impactful.

The Appeal of the Fundamentals

This mixture of art and science is perhaps what attracts us to sports in general. Take for example, the NCAA basketball championship tournament. We can’t ignore the statistics which tell us who his better at certain fundamentals yet, we had little control over who became national champion.

Perhaps that is what attracts people to both sports: that sense of the unpredictability closely wound with the obvious, the pursuit of fundamental excellence and that intangible ambition to win. In running, mastering the fundamentals will always be an indispensible foundation for excellence, it however will go nowhere without a fierce champion’s desire to win.

Fundamentals of Running

We are past March Madness and one thing is quite clear: All of the final teams had excellent fundamentals. Perhaps that is too obvious, given how important dribbling, passing, shooting, and rebounding are to basketball, but the point should not be lost on us - excellent fundamentals make excellent athletes. Such is the same for running.

However, while poor rebounding and missed shots are clear failures to master the fundamentals of basketball- you can see the error right in front of you- the fundamentals of running are not obvious. These fundamentals are subtle because they are the principles of exercise physiology. These four main principles are overload, specificity, individuality and regression.

Overload

We all know exercising the body harder than normal will make it stronger. In exercise physiology terms this is called overload.

This happens in three parts: First exercise, next recovery and finally supercompensation. After recovering to a baseline of fitness, if allowed additional rest time, the body will go onto supercompensate (develop additional strength), which is the body’s natural way of being to prepare to function more efficiently next time. The below graph shows how the body is loaded with stress, recovers, then goes on to supercompensate:¨

In theory, the most efficient way of building fitness relies on balancing workouts against rest and supercompensation, then fitting as many of these cycles into a season as possible. However, in reality, finding that balance can be incredibly difficult.

The body does not give clear signs when it has fully recovered or reached peak supercompensation. Often times, we are left guessing. Combine that guessing with an athlete’s ambition to quickly improve and you have a recipe for disaster.

The problem is caused when an athlete trains again before recovery and supercompensation are complete. This interrupts the overload process, and stagnates their development. This is overtraining 101: Stressing the body again before it has the chance to recover and supercompensate.

So what is the best way to maximize long-term training gains without the impediment of overtraining and injury? It can be tricky to find that perfect point of training balance but some of the best coaches are honing it by taking a more conservative approach. Princeton Head Cross Country and Track Distance Coach Jason Vigilante explains this approach. “I’d rather train everyday at 75% than 4 days in a row at 110%," Vigilante said. "Doing just one more [isn't] always productive.”

Instead of risking overtraining and injury, these coaches deliberately undertrain knowing that they can get bigger returns over the long-term when their athlete’s development does not suffer interruptions from injury and overtraining.

Vigilante goes on to say, “You're not going to take a 4:20 miler to 3:59 overnight… You have to allow them to adapt.”

Some coaches insist on breaking down the athlete through exhausting training. Vigilante says, “I don’t like the tear down process. I just like to be really patient. After a couple of years, they become a successful athlete.” By taking a slightly more conservative approach Vigilante is giving up fast returns but increasing his chances of better long-term development.

Then there's the actual science. The below chart demonstrates stress, rest, and supercompensation at a more conservative pace. Notice by avoiding overtraining, the athlete gets better long-term results. See below:

Specificity

Specificity means specific exercise will bring about specific results (adaptations). Aerobic training will make you more aerobically fit and anaerobic training will make you more anaerobically fit.

This principle is obvious enough, but we often forget to what extent this principle holds true and focus too much on the aerobic benefits of slow jogging; neglecting training at race pace and becoming an athlete that is really good at running a lot (see: jogging).

What’s more, specificity also has strategic significance. Recently, Flotrack spoke with coach Alberto Salazar about his star athlete Galen Rupp. While Rupp is known for training 100+ miles per week, his coach Alberto Salazar makes sure some of his running is focused on sprinting. Rupp routinely includes 400m sprints in his training so that he has the anaerobic power to kick down the competition in the last lap of the 10,000m (see: silver medal from the 2012 London Olympics).

Galen Rupp Workout: All About the Last Lap

“If you’re never running faster than 52 in workouts, then how are you going to run 52 when you are dead tired and you’ve already run 24 laps - it doesn’t make any sense.” – Alberto Salazar

Lastly, specificity also refers to the mode of exercise - The mechanics of the overload. Are you swimming, biking or running? All three can be done aerobically but exercise physiology tells us practicing one mode of exercise has little transferable benefit for the others. Though certain muscles, for example the quadriceps muscles, are active in all three disciplines of swimming, biking and running. They are called upon to perform differently, thus the adaptations and fitness gains will be different.

Salazar keeps with the principle by emphasizing alternative aerobic exercise that closely mimics normal running, like running on the Alter-G and underwater treadmills. Both pieces of equipment lighten the impact of running on the body while still maintaining the biomechanical specificity of running.

Alter-G Treadmill - Alberto Salazar Testimonial

(Full disclosure: This is an infomercial for the manufacturer, but it is still informative)

Underwater Treadmill workout video

(Full disclosure: This is also an infomercial for the manufacturer, but it is still informative)

Athletes with fewer resources can diminish the impact of running by exercising on grass, dirt and woodchips, which are all surfaces that significantly reduce the jarring of running.

Mode specificity is reason enough to stay healthy and stay running because the best way to get better at running is running.

Individuality

Each athlete will adapt differently to the training or the principle of individuality. This is largely a genetic phenomenon, though some individual adaptations are subject to the fitness an athlete has already developed. Individuality states, "The training that returns the best result is training that is tailored to an athlete’s individual strengths."

In a team environment, this is often difficult to achieve. Coach Vigilante elaborates on the difficulty of individual training plans by saying, "To some extent you can look at each undeveloped athlete 'as a seed.' All seeds early on look similar and 'all want to grow and be great,' but you can’t always tell what their makeup is by just looking at them" Vigilante continues, “you don’t know what a kid’s upbringing was, what their foot speed is, their body composition, or personality; there is such an array of differences.”

One athlete in particular that stands out is Princeton middle-distance runner Peter Callahan. Anchor for the recent NCAA Indoor National Championship DMR team and 3:58.76 miler, coach Vigilante says Callahan hasn’t ran more than 25 miles/week this season. Though his mileage might be considered low compared to other athletes, Vigilante goes on to emphasize, “I shouldn’t expect there is consistency between athletes. Each kid has a different set of tools.” It is up to the coach and athlete to make the most of those individual differences.

Regression

The last principle of exercise physiology, regression, is the most depressing.

When an athlete ends regular exercise, fitness is rapidly lost. In one extreme example, a study showed when “subjects were confined to bed for 20 consecutive days [their] V02 max decreased by 25%.” Because of the regression principle, without regular exercise adaptions will quickly erode.

Maintenance – The Sweet Spot

While the regression principle might leave you feeling discouraged, it does come with a caveat: fitness can be maintained if an athlete keeps up some limited training. As long as an athlete maintains the same intensity in their training, they can reduce the frequency and duration of training significantly. This is tapering.

In a taper period, runners are consolidating all potential adaptations and are conceding that they will perform better by resting in the final days before a race than trying to create more adaptations.

The limits of maintenance below:

How often you run (frequency) can be reduced by 2/3, so long as intensity is maintained.

How long you run (duration) can be reduced by 2/3, so long as intensity is maintained.

How hard you run (intensity) must be maintained or fitness gains will reverse.

Honing your ability to maintenance fitness during the taper period will leave you well rested and prepared to give your best possible effort at race day.

Where Exercise Physiology Won’t Take You

For all the science that makes up the fundamentals of training, the sport is also part art. Coach Vigilante states, “You can’t overrule the fundamentals of exercise physiology.” He added, “The fundamentals are art and science.”

He goes on to say, "If I were a genius, [if] I was doing everything correct, and [if] everything was precise, you still haven’t accounted for faith, will, desire; the things that make a champion. There has to be a symbiotic relationship... the art completes a combination of the two.”

Coach Vigilante elaborates, “Some people have been conditioned that winning is everything” and “some people are gentle, so they demur at crunch time. You have to put pressure on some people and take pressure off others.” It’s important to know “what’s going to motivate this kid.”

But at the end of the day, it’s not going to be your success. Sometimes we want success more than our athletes, [but], I can’t do it for you."

Here’s where running becomes more of an art. “Sometimes we need a hug around the head or a kick in the ass,” says Vigilante.

Some athletes need to be given stern instruction and for others you need to let them learn on their own. Explaining how he provides direction to his most ambitious athletes Vigilante concedes, “You can talk to the super motivated Type A personality until you’re blue in the face.” However, “Often you can only communicate via failure.” When the athlete says “Gosh, I’m not succeeding,” that is when a coach’s direction is most impactful.

The Appeal of the Fundamentals

This mixture of art and science is perhaps what attracts us to sports in general. Take for example, the NCAA basketball championship tournament. We can’t ignore the statistics which tell us who his better at certain fundamentals yet, we had little control over who became national champion.

Perhaps that is what attracts people to both sports: that sense of the unpredictability closely wound with the obvious, the pursuit of fundamental excellence and that intangible ambition to win. In running, mastering the fundamentals will always be an indispensible foundation for excellence, it however will go nowhere without a fierce champion’s desire to win.

Related Content

Replay: GVSU Extra Weekend | Apr 25 @ 12 PM

Replay: GVSU Extra Weekend | Apr 25 @ 12 PMApr 26, 2024

How to Watch: 2025 Ascension Seton Austin Marathon and Half Marathon | Track and Field

How to Watch: 2025 Ascension Seton Austin Marathon and Half Marathon | Track and FieldApr 26, 2024

Men's 10k Event 210 - Championship, Finals 1

Men's 10k Event 210 - Championship, Finals 1Apr 26, 2024

Penn Relays 2024 Results On Day 1: See Which NCAA Stars Won

Penn Relays 2024 Results On Day 1: See Which NCAA Stars WonApr 26, 2024

Women's 10k Event 209 - Championship, Finals 1

Women's 10k Event 209 - Championship, Finals 1Apr 26, 2024

Jette Beermann Pushes To Win Women's 5000M Competition At Penn Relays

Jette Beermann Pushes To Win Women's 5000M Competition At Penn RelaysApr 26, 2024

Replay: Paddock - 2024 Penn Relays presented by Toyota | Apr 25 @ 1 PM

Replay: Paddock - 2024 Penn Relays presented by Toyota | Apr 25 @ 1 PMApr 26, 2024

North Carolina Track And Field Stars Win At Penn Relays Year After Wreck

North Carolina Track And Field Stars Win At Penn Relays Year After WreckApr 26, 2024

Men's 5k Event 208 - Championship, Finals 3

Men's 5k Event 208 - Championship, Finals 3Apr 26, 2024