Predictive Value of HS Success in NCAA XC

Predictive Value of HS Success in NCAA XC

Within Greek mythology, there exists a narrative outlining a period of time where both Gods and men co-existed on this Earth, which resulted in some pretty exciting interactions. The Age of Gods and Mortals falls after the Age of the Gods, and I surmise this epoch occurred only because the likes of Dionysus, Hermes, Poseidon, and Athena grew tired of sipping wine, controlling major Earth weather systems, and generally chilling really hard. At this point the otherwise omnipotent, omniscient, and definitively perfect deities decided to engage with mortal humans. For instance, Marsyas (mortal) challenged Apollo (the God of light, truth, archery, song, etc.) to a musical contest involving a double-barreled reed instrument. Marsyas lost, because he was after all challenging a God.

This, in my opinion, is an apt analogy of my collegiate racing career and interaction with the seemingly otherworldly former high school all-stars.

Don’t get me wrong, I worked very hard in college and enjoyed every moment of it. With that being said, to a certain degree, I believed there was a fundamental difference between the former Foot Locker Finalists capable of ripping off 1000 meter repeats in 2:45 as college Freshmen and the runners, like me, who ran just under ten minutes for the two-mile six months prior. In my internally structured schema, there were the athletes who were preordained with the gift of speed, and those who were destined to toil and toil and possibly make a conference team.

This is all changed when I received a text message four weeks ago from my former coach at the University of Portland, Rob Conner.

Rob’s query was simple and straight-forward: How do Foot Locker Finalists perform in college, and more specifically, is there a difference in pedigree between a FL Finalist who finished high, say 4th, versus one who finished lower, say 33rd? This five-minute texting exchange sent me down a labyrinth of twenty-eight races, thirty-four excel tabs, and 3,745 individual athletes.

In order to assess the success attained by former Foot Locker Finalists in the NCAA, I chose to analyze the those high-schoolers who earned a trip to Balboa Park between the years of 2001-2011, and examine how they performed in the NCAA Championship races between the years 2002-2014.

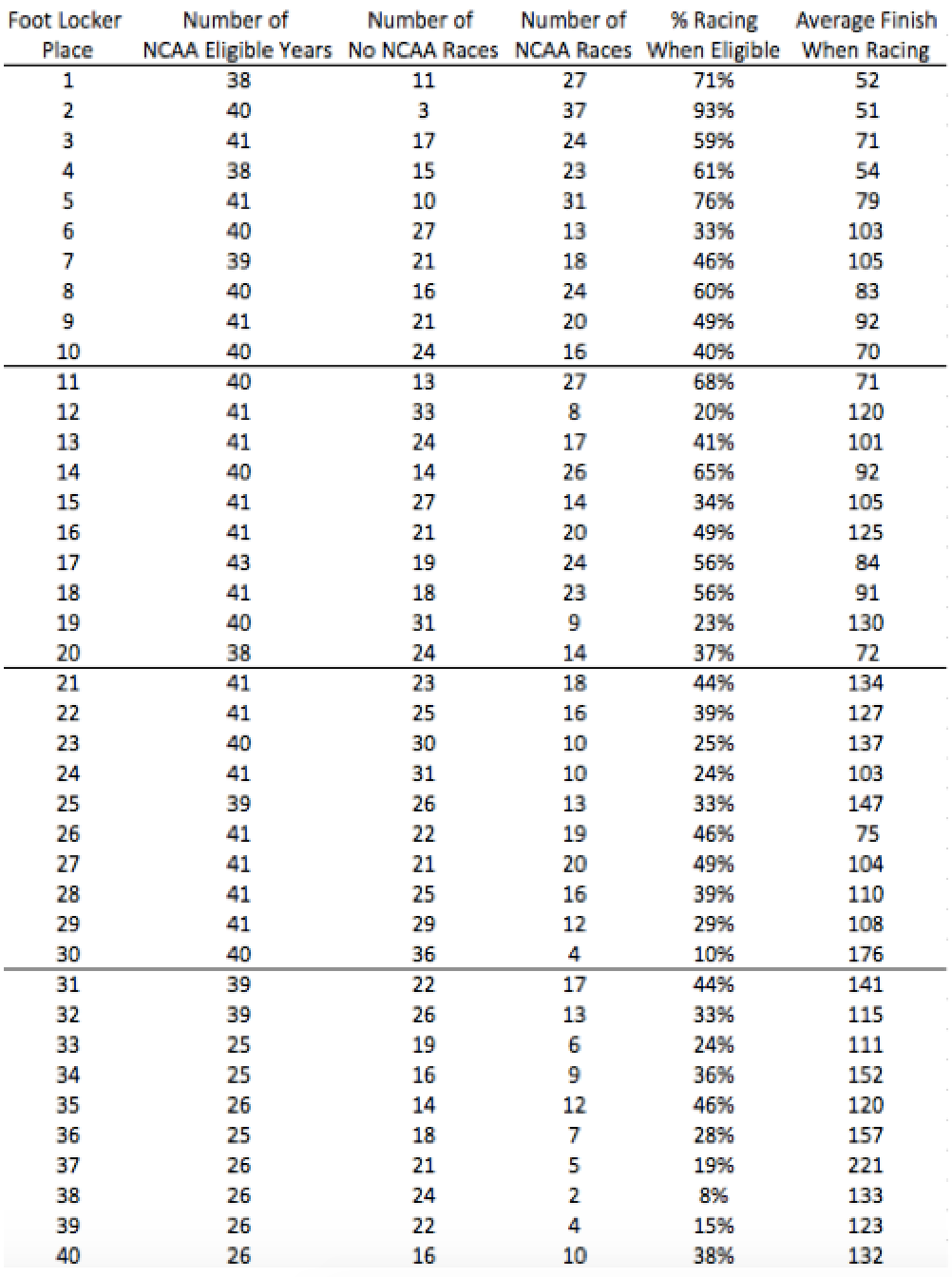

To lay the ground rules for the analysis, the following is my general approach: high school athletes that qualified for Foot Locker are given a five-year window of time for which I searched for their name in Men’s NCAA National Championship results. This window starts after their Senior year in high school. One of these years was a freebie, in that I didn’t hold it against the athlete if one of the years in the window didn’t produce a National Championship appearance, because they either red-shirted or ran attached for all four years right out of college. For instance, Brian Shrader finished 11th at the 2008 Foot Locker Cross Country Championships as a high school Junior. In this instance, his five-year clock would start in the fall of 2010. I used this approach for every Foot Locker racer between the years 2001-2011. Here is the breakdown by Foot Locker finish place:

Notice that there are some fluctuations in the number of eligible college years for each of the aggregated finishing places; this is due to high school Freshmen, Sophomores, and Juniors racing at Foot Locker along with Seniors. Remember, this pushes back their window for analysis. Another item to note is that “eligible years” drops off drastically after 32nd place; this is due to the fact that before 2004, only thirty-two runners raced at the Foot Locker Cross Country Championships, eight from each region.

On its surface, the above table displays some broad trends as you move down the list. Specifically, that the higher up a runner is, the more likely they are to race at NCAA Nationals and the more likely they are to place higher.

Unfortunately, this data is a bit noisy and not particularly helpful. For instance, I really hope no one derives from the table above that it would be better to land an 8th place Foot Locker finisher as an incoming Freshman over a 7th place finisher. The above data shows that over the course of the last fifteen-ish years, 8th place FL finishers race at NCAA Nationals more often and place higher than their 7th place counter-parts.

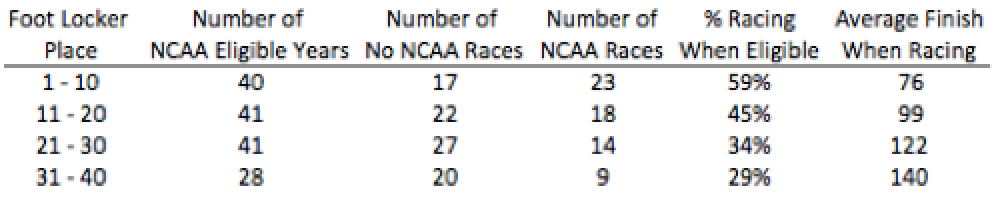

This data is more valuable presented on a more aggregated level, for instance, in four tranches:

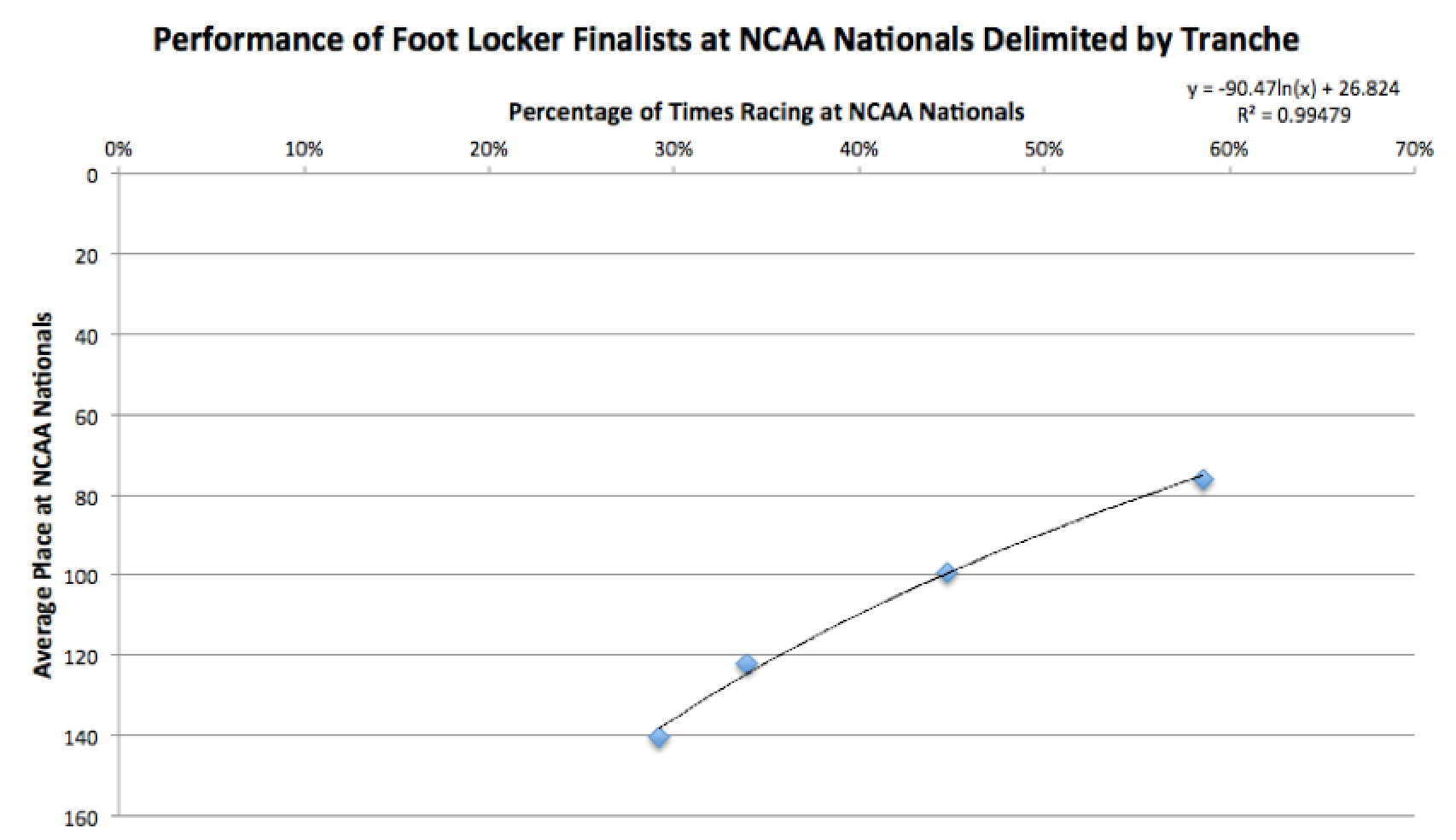

Examining this table, we can see that a more concrete trend exists between finish place at Foot Locker and future performance at NCAA Nationals. To really drive home the correlation, examine our data in chart format with a logarithmic line of best fit included (with bottom-to-top tranches in the above table displayed below from left-to-right):

To break out this information in the most succinct manner possible, we can say that given four years of college eligibility, a top-ten Foot Locker Finisher will race at NCAA Nationals about 2.3 times, averaging 76th place. Athletes that place 11-19 in San Diego go on to race at NCAA nationals an average of 1.8 times (averaging 99th place), and the for the runners finishing between 20-29, they typically race at NCAA Nationals 1.4 times (averaging 122nd). For those finishing between 31st and 40th at Foot Locker, these athlete-scholars typically go on to run at NCAA Nationals about 1.2 times and finish an average of 140th.

As a disclaimer, this data includes several caveats. For instance, included in some of the results are high school Juniors that eventually go on to race at Foot Locker again as Seniors, placing much higher the second time. In this instance, they should not be viewed as any less of a recruit because they did not have a top-ten finish as an underclassman. Furthermore, this data only takes into account NCAA Cross Country performances. There are plenty of runners who raced as a Foot Locker Finalist and had productive collegiate Track & Field careers without racing much at XC Nationals. Take for instance James Cameron, who finished 26th at Foot Locker, did not race at NCAA Cross Country Nationals, but ran a 3:58 mile and 13:51 for 5,000 meters at the University of Washington. Overall, a very successful running career, but almost entirely done on the track.

To isolate the issue with repeat Foot Locker Finalists, I created a database that evaluates the number of athletes who ran at Foot Locker three times, two times, and one time, and populated their respective results. One interesting fact to note before delving into the details is this: 42% of Foot Locker Finalists never race at NCAA Nationals. As in, not once. Ever. Not even a little bit. Clearly there are a lot of factors that go into having a successful collegiate running career, including coaching, teammates, training location. The following approach does a better job of explaining an inherent difference in pedigree between Finalists.

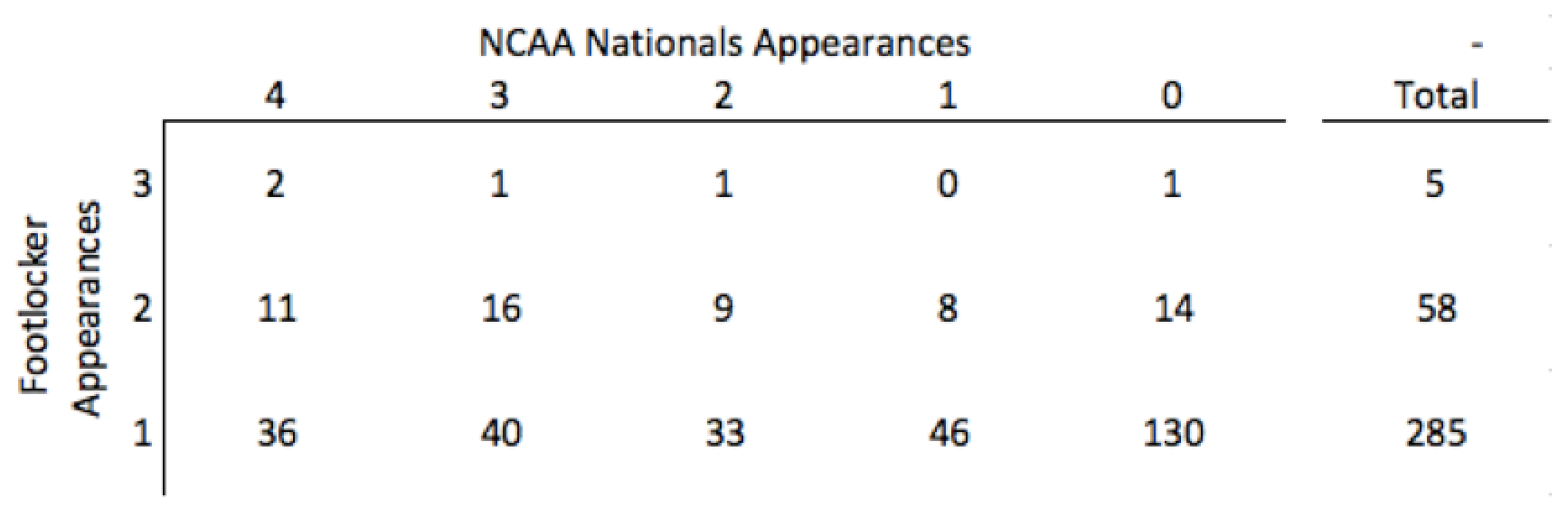

First, let us examine the frequency of NCAA appearances broken down by number of Foot Locker appearances:

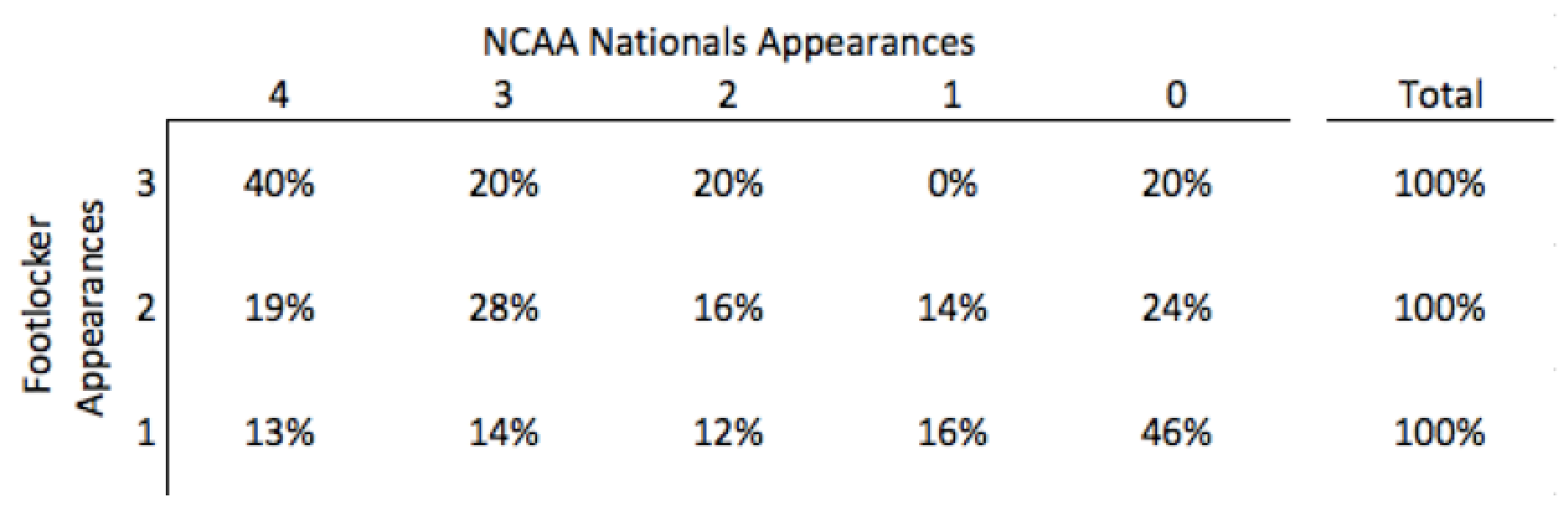

As we can see, the majority of no-shows at NCAA Nationals are committed by one-time Foot Locker Finalists. Here is the same information broken out by percentile rather than nominally:

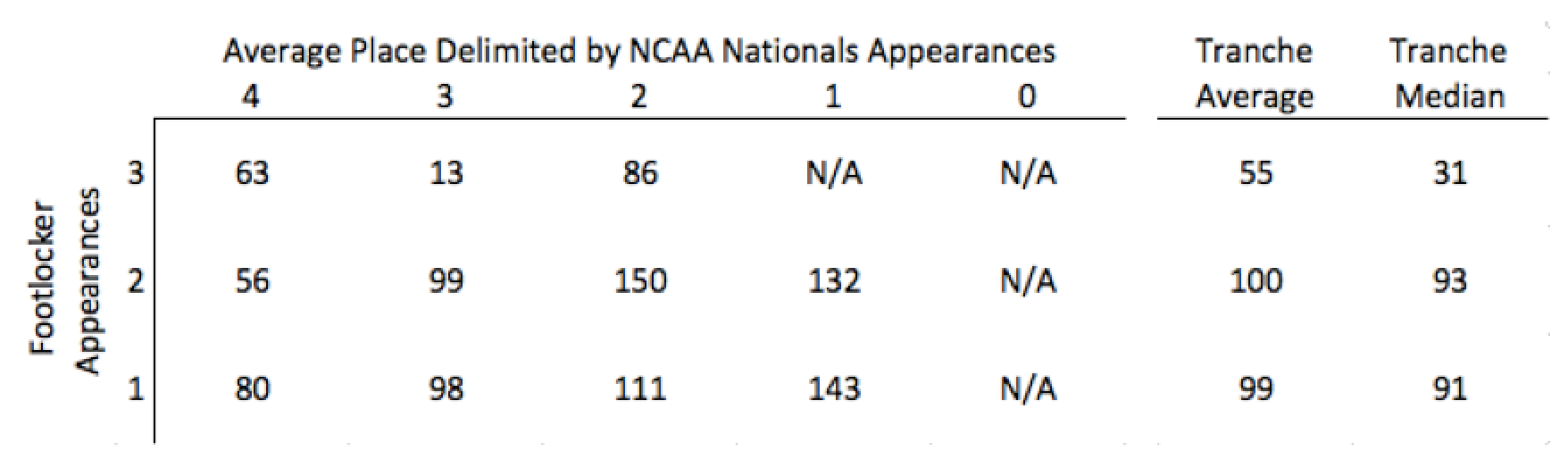

Before jumping to any significant conclusions regarding 20% three-time Foot Locker Finalists never qualifying for NCAA Nationals, remember that only five men made it to FL three separate times between the years 2001-2011. Five instances is a very small population to draw concrete conclusions from. This data is best taken from a broader perspective. Specifically, below is the breakout of average and median place by each tranche of Finalist:

The most interesting thing about this table is the average and median places by athletes racing either twice or once at Foot Locker – they are essentially exactly the same. That is to say, when it comes to place at NCAA Nationals, there really is not a difference between the type of runner who ran at Foot Locker twice rather than once. This ought to be, of course, taken into account with the table we already examined above. Men who qualified for Foot Locker twice have a longer NCAA shelf life, qualifying at least once 76% of the time, where one-time Foot Locker Finalists run at NCAA Cross Country Nationals at least once 54% of the time.

With all of this being said, I would not sleep on one-time Foot Locker Finalists. Here is a list of men who have only qualified once and raced at NCAA Nationals four times: Chris Derrick, Luke Puskedra, Matt Withrow, Stuart Eagon, Hassan Mead, Shadrack Kiptoo-Biwott, Jake Riley, Stephen Pifer, Scott Fauble, and Chris Rombough. The aggregate median place for all four of their NCAA performances is 17th. That is very, very good.

The most salient points to be taken from this exercise are:

1) There is a difference in pedigree with regards to place at the Foot Locker Cross Country Nationals. Finalists who place higher typically go on to qualify more often at the NCAA Cross Country Nationals and usually do better than those who place lower.

2) An athlete that qualifies for Foot Locker more than once typically places higher in the NCAA Nationals races that they qualify for, and they qualify for NCAAs at a higher frequency.

3) There are still plenty of phenomenal athletes that do amazing things in the NCAA that only qualify for Foot Locker once. This segues into my final point, which is:

4) Racing consistently and at a high level in the NCAA is extremely difficult. If this analysis proves any thing, I hope it is that qualifying for Foot Locker is by no means a free pass to being a star in college. There are clearly many contributing factors that lead to a successful NCAA career.

It turns out, after all, that mere mortals have a shot at a place in history along with the high school stars. Or perhaps it is best interpreted that these prep standouts are much more similar to the likes of Marsyas, rather than the deities, just looking for a crack at NCAA prestige along with everyone else.

NUMBERS FOR RUNNING:

11/18/14 Regional Parity: The Variable Nature of the NCAA

10/28/14 120 Minutes Over 26.2 Miles: A Statistical Approach

10/01/14 Unsung Heroes: Third, Fourth and Fifth Runners

09/12/14 By The Numbers: Will Colorado Repeat?

Related Content

Recapping All The Day 1 Action From The Penn Relays At Franklin Field

Recapping All The Day 1 Action From The Penn Relays At Franklin FieldApr 26, 2024

Replay: Penn Relays presented by Toyota | Apr 25 @ 9 AM

Replay: Penn Relays presented by Toyota | Apr 25 @ 9 AMApr 26, 2024

Penn Relays 2024 Schedule Day 2: Here Are Today's Events

Penn Relays 2024 Schedule Day 2: Here Are Today's EventsApr 26, 2024

Replay: GVSU Extra Weekend | Apr 25 @ 12 PM

Replay: GVSU Extra Weekend | Apr 25 @ 12 PMApr 26, 2024

Men's 10k Event 210 - Championship, Finals 1

Men's 10k Event 210 - Championship, Finals 1Apr 26, 2024

Penn Relays 2024 Results On Day 1: See Which NCAA Stars Won

Penn Relays 2024 Results On Day 1: See Which NCAA Stars WonApr 26, 2024

Women's 10k Event 209 - Championship, Finals 1

Women's 10k Event 209 - Championship, Finals 1Apr 26, 2024

Jette Beermann Pushes To Win Women's 5000M Competition At Penn Relays

Jette Beermann Pushes To Win Women's 5000M Competition At Penn RelaysApr 26, 2024

Replay: Paddock - 2024 Penn Relays presented by Toyota | Apr 25 @ 1 PM

Replay: Paddock - 2024 Penn Relays presented by Toyota | Apr 25 @ 1 PMApr 26, 2024