You Were Wrong - Priscilla Lopes-Schliep is Clean

You Were Wrong - Priscilla Lopes-Schliep is Clean

We are so wrong about so many things all the time. For her whole life, Priscilla Lopes-Schliep has been mocked for her veiny and enormous muscles. As a chil

We are so wrong about so many things all the time. For her whole life, Priscilla Lopes-Schliep has been mocked for her veiny and enormous muscles. As a child, her classmates mocked the veins in her legs, as an adult, track fans constantly whispered about doping and once photoshopped a male bodybuilder's head on her body. Her too-good-to-be true physique and Olympic bronze medal in the 100m hurdles led to zealous pursuit from anti-doping authorities, to the point where she was drug tested less than 10 minutes before a World Championship final.

But Lopes-Schliep wasn't doping. She had a rare genetic disorder that was causing her muscles and veins to be extremely defined, though she didn't learn that until very recently. She learned it thanks to an Iowa housewife and muscular dystrophy patient named Jill Viles, who had been doggedly figuring out her own genome for 25 years. As David Epstein put it in his story about the unlikely pair, their story is "basically the plot of the Bruce Willis and Samuel L. Jackson movie 'Unbreakable,'" with Viles in the Jackson role and Lopes-Schliep as Willis. If you're not familiar with the movie, the same gene mutation renders Jackson's bones prone to constant breaking, and Willis' unbreakable.

In addition to giving Lopes-Schliep proof of the innocence she's always maintained, Viles also may have saved her life. When Lopes-Schliep's doctors confirmed that she had the disorder, they also discovered that she had three times the normal amount of fat in her blood, and immediately put her on a restricted diet. This was the second time that Viles' amateur medical research saved a life; when she figured out that her father had the same disease she did, and he was weeks away from a heart attack.

There are a million things to take away from this story, most of which don't have to do with sports. But as an extremely skeptical sports fan, this is the most important: great athletes often really do have genes that help them do unbelievable things. The next time I see an athlete and think to myself that she's doping, this story will remind me to at least consider the possibility that she might not be.

Epstein brought Viles and Lopes-Schliep together and reported their shocking true story for ProPublica and This American Life. Below is an in-depth interview with the writer and reporter:

FloTrack: People, even people who know a decent amount of science, must give themselves crackpot diagnoses all the time. How floored were you when you found out that this woman had correctly diagnosed herself with two incredibly rare genetic disorders in 25 years, and saved at least two lives, mostly by using library books and Google Images?

David Epstein: It kind of seems like if you get to the second page of Google results these days that can count as deep research. (Which is a great competitive advantage for me, because if I find something in some old manuscript in a library, I can be pretty sure I'll never have to worry about anyone else finding it!) And I think it can be a burden for doctors at times to have that kind of "the patient will see you now" mentality to deal with. Even very bright people will tend to go astray researching their own conditions. With limited knowledge, they're going to fit things into a tidy story no matter what. "I don't know yet" doesn't sit well with most people. So, ya know, I was wary when I heard from Jill, but in some ways it was her acknowledgement of this as a long shot that made me a little more accepting that she wasn't a crazy person. And the more I learned about her, the more impressed I was.

It certainly surprised me that she stuck with this, but part of me also got it on some level. I was a grad student in geological sciences in my past life, and I got a better education in genetics reporting The Sports Gene than I got in earth science in grad school. (Except for the part that I wouldn't know how to run the lab machines in a genetics lab, where I did know how to use tech in a geology and plant physiology lab). But I guess my career has made me well aware that bright, determined people can develop specialized knowledge that almost wouldn't make sense for anyone else to have. And I first got into journalism at all to write about my friend and training partner who dropped dead after a mile race--the chapter about sudden death is the most meaningful to me, even though it didn't get as much attention as 10,000 hours and all that--and that brought me to the community for a particular disease, and I learned there that people with rare diseases may have seen more people with the disease in their own family than most or any researcher has, ever. They become visual experts, the same expertise that baseball players develop for recognizing pitches unconsciously. So I guess none of the individual components of Jill's feat felt impossible to me, but I absolutely just doubted that they had all come together in this woman who heard me yammering on Good Morning America about sports and genetics and decided to send a letter. I mean, the angle with Priscilla, that seemed pretty fanciful when I first saw it. I didn't even think we'd get a serious response from Priscilla, to be honest. But she is one cool character.

I hope she becomes the sixth athlete ever to medal in the Summer and Winter Games.

On the flip side of that, did this story make you reconsider people's stories of getting blithely dismissed by their doctors?

It did. Let me first say, though, that in most cases the doctor will be right. They're balancing the odds with their intuition and knowledge. Aside from doctors, it made me think about so many of the letters I've gotten from readers over the years. How often did I pass up what might've been a worthy story? I mean, you just can't take them all on, or even close, but it can be hard to tell sometimes the difference between the seed of something great and some fanciful theory. I will say, Jill's approach made it pretty impossible for someone like me to ignore her. She had a great subject line in her email, did a great "tease," so to speak, introduced herself quickly, and showed that she had taken time to read my work, so I knew it wasn't a form letter or email she was using to blanket journalists.

I can't tell you how many ill-targeted pitches I get. It's incredible. Right now, I'm staring at a pitch in my inbox about a particular, supposedly special kind of candy. Not only does the person pitching clearly have no clue that this would never fit in the places I write for, but, honestly, I'm sure they don't actually want me writing about this, because it'd be far more likely I'd end up on an investigative path than a laudatory one if I start to research a candy that is making special claims...

Somehow, that's all to say that doctors have a difficult job in the age of what they sometimes call the "Google and go" patient, because they have to sift through mostly ideas that, while well intentioned, are just wrong. But maybe it's also important to try to be discerning about the person coming your way, and to realize that Jill was researching and presenting her case in an atypically astute manner that deserved consideration. And, by the way, she did want to tell me that her local physician in Gowrie, Iowa--Dr. Adam Swisher--kept encouraging her. He wasn't by any means a specialist in these rare diseases, but apparently recognized that she had developed some special knowledge, and just encouraged her to keep going. I think that meant a lot to her, and it came from her local doctor, not some of the national and international experts who had told her she was on the wrong track. Maybe with Dr. Swisher it was kind of like the coach/athlete relationship. It often isn't so much about being the leading expert in some particular aspect of the sport or physiology, but some level of knowledge that--when combined with knowing your athlete and with compassion and humility--helps you give them the right push in the right way.

This story started when Jill read your book and sent you a package asking for your take on her genes. Can you give me any particularly insane examples of reader mail you've received since The Sports Gene came out?

[ed. note: BUY AND READ THIS BOOK]

Well, she didn't so much want my take on her genes exactly as she wanted to share her theory and see if I found it interesting enough to help her reach out to Priscilla on her behalf and see if we could confirm it.

But, yeah, as far as crazy email after The Sports Gene…I loved the fact that most of the mail was really cool, people sharing their own stories or observations, and it was great. But there was indeed some silly stuff. I remember one email from a bodybuilder who was saying he'd read chapter six, the one about "Superbaby" and muscle building genes, and that he had the very rare muscle-exploding gene mutation I was writing about, but that all the rest of his competitors were on steroids. The funniest part is that it came up in conversation with a scientist who told me he happened to have included this guy in a study, and the guy certainly did not have the mutation. None of the bodybuilders in the study did. But apparently the guy was intent on continuing to say he was a supermutant and everyone else is cheating.

As a sports fan, it kind of ate at my conscience a little that the thing that helped make Priscilla Lopes-Schliep one of the best hurdlers in the world was also a rare, difficult to detect, and potentially fatal disorder. Can you think of any other examples of that in sports? The closest that I can think of is Marfan syndrome and giant basketball players, which was probably going undetected a few decades ago. But the NBA is pretty good at catching that now.

Marfan is a great example. And there are other conditions that can contribute in that way to very unusual stature, like having a pituitary tumor that makes you secrete too much growth hormone. There are NBA players who have had that as well. There's a genetic mutation that causes something called Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, which makes people hyper flexible, and one scientist mentioned to me that he thought it might help certain types of physical performers, but maybe more like the folks who fold themselves into boxes at the circus. The reindeer farmer/gold medalist I wrote about in the last chapter of The Sports Gene had a form of polycythemia--way more than the normal portion of red blood cells, basically. That can be dangerous for some people, but those in his family who had it tended to live completely normal lives. Although he himself did go on blood thinners very late in life. And back to that bodybuilder, the only known adult with the mutation he was talking about--on the myostatin gene--was a pro sprinter. Her baby has two copies of the rare mutation and came really muscular, and I know doctors were concerned that his heart may grow abnormally, but I'm not sure where that stands right now.

One part that really stuck with me was when Lopes-Schliep told you that her musculature led to constant accusations of doping and invasive, illegally administered drug tests. Like most sports writers, I have a private list of athletes that I think are doping, and I imagine you do too. What did you think about Lopes-Schliep before reporting this story? I know from reading your book that you have more of an imagination for genetic outliers than just about anyone else in sports writing, but did you consider this as a possibility?

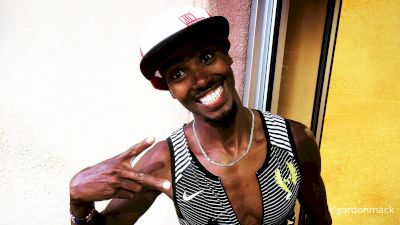

I certainly knew who she was and had noted her physique years ago just watching her race. And even when she's just standing around next to other sprinters, you can see the difference in terms of how prominent the divisions in her muscles are--check this out. One sports writer I talked to about her put it, "how could you not suspect steroids?" And that's fair given where we are in sports generally. At the same time, I was aware that there are a whole bunch of conditions that can account for unusual physique, and that it can be especially noticeable in women. I didn't know that partial lipodystrophy could manifest quite this way, though, nor really did doctors I spoke with. The world's expert in the condition said he did see unusually muscular patients, and a number had gone on to be high level athletes, but that Priscilla is at the extreme.

But Lopes-Schliep wasn't doping. She had a rare genetic disorder that was causing her muscles and veins to be extremely defined, though she didn't learn that until very recently. She learned it thanks to an Iowa housewife and muscular dystrophy patient named Jill Viles, who had been doggedly figuring out her own genome for 25 years. As David Epstein put it in his story about the unlikely pair, their story is "basically the plot of the Bruce Willis and Samuel L. Jackson movie 'Unbreakable,'" with Viles in the Jackson role and Lopes-Schliep as Willis. If you're not familiar with the movie, the same gene mutation renders Jackson's bones prone to constant breaking, and Willis' unbreakable.

In addition to giving Lopes-Schliep proof of the innocence she's always maintained, Viles also may have saved her life. When Lopes-Schliep's doctors confirmed that she had the disorder, they also discovered that she had three times the normal amount of fat in her blood, and immediately put her on a restricted diet. This was the second time that Viles' amateur medical research saved a life; when she figured out that her father had the same disease she did, and he was weeks away from a heart attack.

There are a million things to take away from this story, most of which don't have to do with sports. But as an extremely skeptical sports fan, this is the most important: great athletes often really do have genes that help them do unbelievable things. The next time I see an athlete and think to myself that she's doping, this story will remind me to at least consider the possibility that she might not be.

Epstein brought Viles and Lopes-Schliep together and reported their shocking true story for ProPublica and This American Life. Below is an in-depth interview with the writer and reporter:

FloTrack: People, even people who know a decent amount of science, must give themselves crackpot diagnoses all the time. How floored were you when you found out that this woman had correctly diagnosed herself with two incredibly rare genetic disorders in 25 years, and saved at least two lives, mostly by using library books and Google Images?

David Epstein: It kind of seems like if you get to the second page of Google results these days that can count as deep research. (Which is a great competitive advantage for me, because if I find something in some old manuscript in a library, I can be pretty sure I'll never have to worry about anyone else finding it!) And I think it can be a burden for doctors at times to have that kind of "the patient will see you now" mentality to deal with. Even very bright people will tend to go astray researching their own conditions. With limited knowledge, they're going to fit things into a tidy story no matter what. "I don't know yet" doesn't sit well with most people. So, ya know, I was wary when I heard from Jill, but in some ways it was her acknowledgement of this as a long shot that made me a little more accepting that she wasn't a crazy person. And the more I learned about her, the more impressed I was.

It certainly surprised me that she stuck with this, but part of me also got it on some level. I was a grad student in geological sciences in my past life, and I got a better education in genetics reporting The Sports Gene than I got in earth science in grad school. (Except for the part that I wouldn't know how to run the lab machines in a genetics lab, where I did know how to use tech in a geology and plant physiology lab). But I guess my career has made me well aware that bright, determined people can develop specialized knowledge that almost wouldn't make sense for anyone else to have. And I first got into journalism at all to write about my friend and training partner who dropped dead after a mile race--the chapter about sudden death is the most meaningful to me, even though it didn't get as much attention as 10,000 hours and all that--and that brought me to the community for a particular disease, and I learned there that people with rare diseases may have seen more people with the disease in their own family than most or any researcher has, ever. They become visual experts, the same expertise that baseball players develop for recognizing pitches unconsciously. So I guess none of the individual components of Jill's feat felt impossible to me, but I absolutely just doubted that they had all come together in this woman who heard me yammering on Good Morning America about sports and genetics and decided to send a letter. I mean, the angle with Priscilla, that seemed pretty fanciful when I first saw it. I didn't even think we'd get a serious response from Priscilla, to be honest. But she is one cool character.

I hope she becomes the sixth athlete ever to medal in the Summer and Winter Games.

On the flip side of that, did this story make you reconsider people's stories of getting blithely dismissed by their doctors?

It did. Let me first say, though, that in most cases the doctor will be right. They're balancing the odds with their intuition and knowledge. Aside from doctors, it made me think about so many of the letters I've gotten from readers over the years. How often did I pass up what might've been a worthy story? I mean, you just can't take them all on, or even close, but it can be hard to tell sometimes the difference between the seed of something great and some fanciful theory. I will say, Jill's approach made it pretty impossible for someone like me to ignore her. She had a great subject line in her email, did a great "tease," so to speak, introduced herself quickly, and showed that she had taken time to read my work, so I knew it wasn't a form letter or email she was using to blanket journalists.

I can't tell you how many ill-targeted pitches I get. It's incredible. Right now, I'm staring at a pitch in my inbox about a particular, supposedly special kind of candy. Not only does the person pitching clearly have no clue that this would never fit in the places I write for, but, honestly, I'm sure they don't actually want me writing about this, because it'd be far more likely I'd end up on an investigative path than a laudatory one if I start to research a candy that is making special claims...

Somehow, that's all to say that doctors have a difficult job in the age of what they sometimes call the "Google and go" patient, because they have to sift through mostly ideas that, while well intentioned, are just wrong. But maybe it's also important to try to be discerning about the person coming your way, and to realize that Jill was researching and presenting her case in an atypically astute manner that deserved consideration. And, by the way, she did want to tell me that her local physician in Gowrie, Iowa--Dr. Adam Swisher--kept encouraging her. He wasn't by any means a specialist in these rare diseases, but apparently recognized that she had developed some special knowledge, and just encouraged her to keep going. I think that meant a lot to her, and it came from her local doctor, not some of the national and international experts who had told her she was on the wrong track. Maybe with Dr. Swisher it was kind of like the coach/athlete relationship. It often isn't so much about being the leading expert in some particular aspect of the sport or physiology, but some level of knowledge that--when combined with knowing your athlete and with compassion and humility--helps you give them the right push in the right way.

This story started when Jill read your book and sent you a package asking for your take on her genes. Can you give me any particularly insane examples of reader mail you've received since The Sports Gene came out?

[ed. note: BUY AND READ THIS BOOK]

Well, she didn't so much want my take on her genes exactly as she wanted to share her theory and see if I found it interesting enough to help her reach out to Priscilla on her behalf and see if we could confirm it.

But, yeah, as far as crazy email after The Sports Gene…I loved the fact that most of the mail was really cool, people sharing their own stories or observations, and it was great. But there was indeed some silly stuff. I remember one email from a bodybuilder who was saying he'd read chapter six, the one about "Superbaby" and muscle building genes, and that he had the very rare muscle-exploding gene mutation I was writing about, but that all the rest of his competitors were on steroids. The funniest part is that it came up in conversation with a scientist who told me he happened to have included this guy in a study, and the guy certainly did not have the mutation. None of the bodybuilders in the study did. But apparently the guy was intent on continuing to say he was a supermutant and everyone else is cheating.

As a sports fan, it kind of ate at my conscience a little that the thing that helped make Priscilla Lopes-Schliep one of the best hurdlers in the world was also a rare, difficult to detect, and potentially fatal disorder. Can you think of any other examples of that in sports? The closest that I can think of is Marfan syndrome and giant basketball players, which was probably going undetected a few decades ago. But the NBA is pretty good at catching that now.

Marfan is a great example. And there are other conditions that can contribute in that way to very unusual stature, like having a pituitary tumor that makes you secrete too much growth hormone. There are NBA players who have had that as well. There's a genetic mutation that causes something called Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, which makes people hyper flexible, and one scientist mentioned to me that he thought it might help certain types of physical performers, but maybe more like the folks who fold themselves into boxes at the circus. The reindeer farmer/gold medalist I wrote about in the last chapter of The Sports Gene had a form of polycythemia--way more than the normal portion of red blood cells, basically. That can be dangerous for some people, but those in his family who had it tended to live completely normal lives. Although he himself did go on blood thinners very late in life. And back to that bodybuilder, the only known adult with the mutation he was talking about--on the myostatin gene--was a pro sprinter. Her baby has two copies of the rare mutation and came really muscular, and I know doctors were concerned that his heart may grow abnormally, but I'm not sure where that stands right now.

One part that really stuck with me was when Lopes-Schliep told you that her musculature led to constant accusations of doping and invasive, illegally administered drug tests. Like most sports writers, I have a private list of athletes that I think are doping, and I imagine you do too. What did you think about Lopes-Schliep before reporting this story? I know from reading your book that you have more of an imagination for genetic outliers than just about anyone else in sports writing, but did you consider this as a possibility?

I certainly knew who she was and had noted her physique years ago just watching her race. And even when she's just standing around next to other sprinters, you can see the difference in terms of how prominent the divisions in her muscles are--check this out. One sports writer I talked to about her put it, "how could you not suspect steroids?" And that's fair given where we are in sports generally. At the same time, I was aware that there are a whole bunch of conditions that can account for unusual physique, and that it can be especially noticeable in women. I didn't know that partial lipodystrophy could manifest quite this way, though, nor really did doctors I spoke with. The world's expert in the condition said he did see unusually muscular patients, and a number had gone on to be high level athletes, but that Priscilla is at the extreme.