2017 IAAF World ChampionshipsAug 10, 2017 by Johanna Gretschel

From DII To World Team: The Improbable Rise Of Quanera Hayes & Drew Windle

From DII To World Team: The Improbable Rise Of Quanera Hayes & Drew Windle

Quanera Hayes and Drew Windle ran for NCAA Division II colleges and now they're on the world team. How?

"So, why didn't you go pro?"

That was the question I got after an hour of chatting with Quanera Hayes -- the reigning U.S. champion in the 400 meters, bronze medalist in the 2016 World Indoor Championships, American record holder for 300m, and a member of the American contingent at this summer's IAAF World Championships in London.

We sat on yellow chairs in the pristine white marble lobby of the Breezes Resort & Spa in Nassau, Bahamas, one of the designated athlete hotels for the IAAF World Relays this past April. Hayes was there as a member of the Team USA 4x400 relay that would win gold later that weekend.

She asked me why I didn't go pro when I told her I was a former collegiate middle distance runner. Even after I explained how far off my times were from making the NCAA regionals -- much less the USATF Championships -- she laughed it off. Hayes seemed to suggest that deciding to go pro was just that -- a decision, available to anyone with enough devotion to the craft.

That kind of resolve might have been what brought her to London.

Out of 136 Americans named to the world team, 127 competed for NCAA Division I universities. Of the qualifiers, 14 started in the junior or community college ranks before jumping up to Division I. The qualifiers who competed in Division II and NAIA are almost exclusively race walkers or field athletes.

Hayes is an exception. Another is middle distance runner Drew Windle, who was one of the biggest surprises of the U.S. Championships with his third-place, come-from-behind finish in the men's 800m.

Neither Hayes nor Windle made the world final in their respective event, but both athletes navigated well through the first two rounds in London. Hayes' medal hopes are still alive, as she will likely race on Team USA's 4x400m relay in the prelims on Saturday morning. The finals will close out the 2017 competition on Sunday evening.

"I feel like I always knew I was gonna go pro in a sport," Windle tells me over the phone. "But I always imagined I would be playing for the Green Bay Packers."

When Windle was a senior in high school, he stood at 6-foot-3 and weighed 20 pounds heavier than his current 165. He wanted to play tight end, and was considering the football programs at Ashland University and Tiffin University -- two Division II schools in Ohio -- when Trent Mack, Ashland's distance coach, saw some footage of Windle running the 200m in a relay.

When Mack describes Windle, he describes every coach's dream: a "competitive" and "grinding" bundle of raw hunger.

He wanted Windle for the track -- not the (football) field.

He wanted Windle for the track -- not the (football) field.

As Windle came around to the idea of focusing on track during his senior year in high school, his time in the 800m dropped dramatically: from a pedestrian 1:57 to a personal best of 1:51.94 at the Ohio state championship to win his one and only state title.

People noticed. And it wasn't just Mack -- who had convinced the burgeoning star to forego football and focus solely on track.

"I heard there were some bigger schools interested in me after the state meet," Windle says. "[But] I talked to the coach at Ashland and my parents and I thought I already had a pretty good thing established. 'Let's stick it out' . . . that was my gut decision."

For Windle, it was about commitment. He resisted the overtures of Division I schools and made the choice to stand by his pledge to Ashland.

"I think he brought it up before I did," Mack remembers. "He told me, 'I want to reassure you that I'm happy with my decision.'"

Like Windle, Hayes flew under the radar her senior year of high school. She ran the 400m and 200m with consistent times around 60 and 25 seconds, respectively.

Justin Davis, the head coach at Livingstone College in Salisbury, North Carolina, first noticed Hayes while attending a local high school meet to scout potential recruits.

"I wasn't looking for anything in particular," he says. "But when I saw her race that day, she won both of her events with pretty fast hand times and was winning pretty significantly. . . [but] wasn't on a lot of people's radars."

"I wasn't looking for anything in particular," he says. "But when I saw her race that day, she won both of her events with pretty fast hand times and was winning pretty significantly. . . [but] wasn't on a lot of people's radars."

Like Windle, Hayes was verbally committed to Livingstone at the North Carolina state meet before blowing out her personal best with a 56.46 in the 400m, the fastest of any athlete in the prelims.

Although she placed fourth in the final with a 58.06 effort -- she was drained after anchoring her second-place 4x200m relay -- her drop in time caught the eyes of bigger schools. Hayes considered NC State, North Carolina A&T, UNC Greensboro, and UNC Charlotte.

Livingstone, however, remained the most desirable choice for Hayes because of academic standards. Division II universities can be more forgiving when it comes to academic requirements for admission, and Hayes was short a math credit. Livingstone was the only school that still offered her a partial scholarship even though she would have to take an academic redshirt.

"That was the best decision," Hayes says. "My plan was to get a scholarship . . . they were the only school who would give me a scholarship even though I would have to sit out."

Hayes would eventually become one of the most decorated athletes in Livingstone's history.

"By the grace of God we were able to get her," Davis says. "Sometimes DII is a strange area. . . you either choose DII or it chooses you."

When Hayes won her first national title as a redshirt sophomore, she crossed the line in 51.54.

She had never broken 53 seconds before that race.

Not only was she Livingstone's first female NCAA champion, but she would eventually become the first woman from any Division II school to win three consecutive NCAA outdoor 400m titles.

"That was crazy for me," Hayes remembers. "I was so shocked. I don't know. . . I had never won anything big in my entire life. I never won a state championship. I finally felt that I had accomplished something that I've been waiting for for a very long time."

Her coach was shocked, too.

"I was a pretty young coach at the time," Davis says. "When she crossed the line and I saw that time, my body went numb. To be the head coach and to experience my first national champion and a time that matched up with any athlete in the nation . . . it was just amazing."

Hayes' time would have made her an All-American at the Division I Championship and many bigger schools took note.

"A lot of [DI] coaches came to me," she says. "I actually wanted to go to the University of South Carolina. It was very overwhelming."

She had old friends at South Carolina, and Hayes thought seriously about joining them in Columbia, but her mother and coaches encouraged her to stay with Livingstone's small setting in Salisbury to keep on track with her academics.

She had old friends at South Carolina, and Hayes thought seriously about joining them in Columbia, but her mother and coaches encouraged her to stay with Livingstone's small setting in Salisbury to keep on track with her academics.

"That's what the Division II model is about: balancing academics and athletics," Davis says.

By her junior year, Hayes had formed a tight-knit community between her track teammates and her sorority, Alpha Kappa Alpha, which made it easier to accept the decision.

"Those are my sisters," she says of her AKA friends. "I would've had to start over at another school. That's why it wasn't as hard and I wasn't as upset to stay. I did have a whole life at Livingstone."

Ultimately, she feels it was the right decision.

"I still got my education," she says. "I was still able to compete. I was still able to go pro. I had everything I really needed. . . I wasn't another number in my division, in my conference. I had a name for myself."

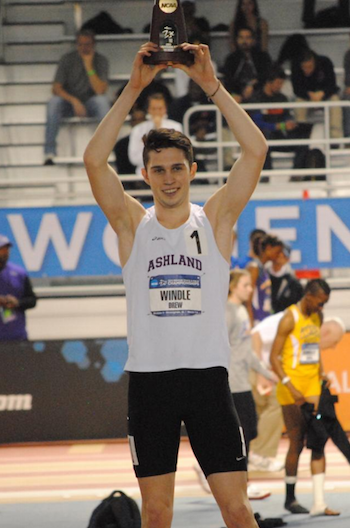

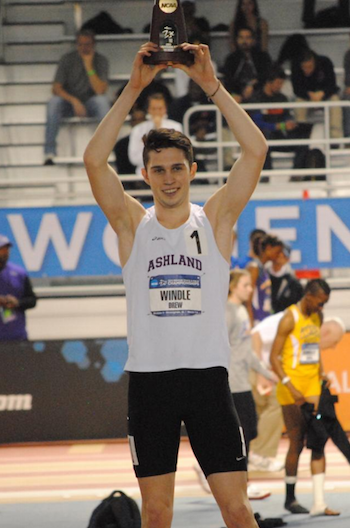

Windle's 2013 NCAA Indoor 800m title was the first of his six consecutive NCAA Championship wins in the distance. He also helped the Eagles win national titles in the 4x400m relay and distance medley relay.

Mack, his coach, points to a comical moment at the NCAAs during Windle's freshman year as the catalyst for his future success.

Mack, his coach, points to a comical moment at the NCAAs during Windle's freshman year as the catalyst for his future success.

"He'll kill me for saying this," Mack says. "But with two laps to go to in the prelims at the indoor national meet as a freshman, he makes a pretty strong move and gaps the field a little bit. He held the move and I was like, 'What is he doing?' I'm starting to worry here, he runs about half a lap pretty aggressively and settles back in and the field catches back up and I'm like, 'Oh my goodness, what is going on?' He finished and just made the finals. He came up to me afterwards with a little smirk on his face and he's like, 'I miscounted the laps!'"

Windle took sixth in 1:54.03 -- his first of 10 All-American honors.

Windle wanted to break 1:50 his freshman year, a goal Mack deemphasized in favor of honing race tactics.

"We talked about not putting so much focus the first year on time, but learning how to race at the championship level," Mack says. "He didn't break 1:50 as a freshman but he ran 1:50 three times, and that was a big factor setting him up for his second year, where I think he skipped 1:49 altogether."

At the 2013 NCAA DII Indoor Championships, Windle ran 1:50 in the prelims and 1:48.75 in the final to win by two full seconds for his first national title. He repeated the feat at outdoor nationals, and, once again -- like his breakthrough performance at the Ohio state meet -- questions arose of whether or not Windle would ditch his DII program for a DI school.

"When I won my first two titles in the 800m my sophomore year, people were like, 'You should transfer to a bigger DI school and see what you can do there,' but I was happy at Ashland," he says. "Running in Division II made me learn how to be a consistent racer and learn my ideal style of racing a lot quicker."

Both Windle and Mack agree that it can be a pro and a con that DII athletes don't see as much competition.

"The biggest program doesn't mean that's your opportunity to run and compete to the best of your ability," Mack says. "Even thinking about the social environment . . . At times, Drew is very quiet, and I think a smaller campus size was a great fit for him and that's a big part of it that you have to really know about yourself and answer truthfully."

Windle was sitting in a night class in October of his senior year when he was startled from the doldrums of his English elective by a direct message on Twitter from Brooks Beasts head coach Danny Mackey.

"Somebody was presenting at the front of the class and I just got up and went to the bathroom," Windle remembers. "I just had to collect myself and realize what was happening in that moment."

Windle had lowered his personal best to 1:46 as a junior, and he planned to pursue a professional running career after graduation. He just wasn't sure how.

"I knew that 1:46 from a small school would stick out a little bit, but I didn't really know how the process [of turning pro] worked."

The two continued to chat every few weeks throughout the school year. In the spring, Windle graduated and went up to Oregon to compete at the Portland Track Festival, where he met up with the Beasts' Cas Loxsom. The two drove to Seattle together -- where the Beasts are headquartered -- and Windle spent about a week and a half with the team before USAs.

FloTrack interviewed Windle after he won his sixth straight NCAA Division II 800m title:

Mackey says he first took note of Windle at the 2014 USATF Championships from a story that Loxsom told him. The kid who nobody had heard of from the school nobody had heard of ran the fourth-fastest time in the prelims to make the semifinal, but he did it while racing in full tights because he had forgotten his shorts. And as if that wasn't enough, the kid had accidentally walked three miles to the stadium before the event because he didn't know how far away it was from his hotel.

"I really liked two things," Mackey says. "One, he seemed very level-headed and positive from the conversations I had with him, and, two, from a racing standpoint, even though he was Division II, he seemed like a very quiet competitor--someone I could easily work with who would be a strong addition to the team who had a big way of improving."

He believes the DII roots gave Windle grit and gratitude.

"At Division II schools, you don't really get anything," Mackey says. "You don't get shoes, you a get a shitty kit, your travel budget sucks. I have worked with some athletes that are entitled and feel like nothing is good enough. The grass is always greener. He's got a lot of humility.

"On the racing side of things, he's learned how to win. That's an abstract trait and maybe he was just better than everybody else and didn't have to work as hard, but if you look at his races, he knows how to win."

Nick Symmonds, a former Brooks Beast who retired from the sport this year, echoes Mackey's sentiment.

The 2013 world silver medalist would know, as he is also a product of a non-Division I program, having won seven NCAA titles at Willamette University, a Division III institution.

"[Head coach] Kelly Sullivan, when he brought me to Williamette, he said, 'You're gonna be the best athlete in every race and probably best athlete in DIII and you need to develop a taste for winning," Symmonds says. "You need to be able to win slow races, fast races, win when you get bumped, win when you get elbowed, win when you trip.' And I never lost in my collegiate running career.

"I took that winning mentality, that addiction to winning, with me when I became a pro. You see that same thing in Drew: he's won [lots of DII titles] and had a taste for winning. If you go to DI and you never win a race and you're always fighting for third or fourth, you're not addicted to winning. You start to settle, 'Oh, I'm a mid-packer,' and you think that's ok. You don't understand what it means to be a winner."

Drew Windle finally got to race Brooks Beasts mentor Nick Symmonds in the preliminary round of the 800m at USAs this year:

Hayes was more relevant on the U.S. senior level right away, as she placed fifth in the USATF final a few weeks after her college graduation.

"The only people to beat her were former Olympians and world champions," her agent, Charles Wells of Trident Sports Management, says now. "We definitely had something real awesome on our hands."

Wells is a former Division II athlete himself and was actually teammates at Texas A&M - Kingsville with high jumper Jeron Robinson, one of the few DII products to represent Team USA at the World Championships this year. His background gave him added interest in Hayes and he signed her immediately following graduation.

But it still took her nearly a year to pick up a shoe sponsor.

Hayes moved to Clermont, Florida, as she had always told herself she would only turn pro if she moved to the Sunshine State. She didn't join one of Clermont's training groups, though. She took direction from Derrick White of Life Speed Athletics, but preferred to train on her own.

"It was hard, very hard," she says of her year training without a sponsor. "I was training full-time. Nobody wanted me to get a job, I tried to but my mom and my coach at the time kept saying, 'No, just wait, it'll happen.' I just kept working hard and I knew it would come eventually if I could stay focused."

She was also alone in Florida, 600 miles away from everyone she'd ever known. Thanksgiving was particularly hard, and she broke down in tears at practice after her mom -- who was briefly visiting -- left to go back home for the holiday. Her coach was also away on vacation with family and his friend was at the track to help her with the workout, though he ended up helping in a different way by giving her the phone number of a girl he knew -- Chelsea -- who was Hayes' age. Now, she had an ally.

"She's one of my best friends now," Hayes says. "I explain a lot of stuff to her about what I go through and what I do as a professional track and field athlete because she didn't know anything about that. All she really knows is that I'm a professional athlete and run really fast and she knows I run a 400m."

The struggle through the fall yielded massive gains in the spring, as Hayes won the USATF Indoor National Championship in the 400m and qualified to represent Team USA at the IAAF World Indoor Championships in Portland, Oregon.

Quanera Hayes speaks to the media after winning the 2016 USATF Indoor Championships 400m:

At World Indoors, he quartet of Hayes, Natasha Hastings, Courtney Okolo, and Ashley Spencer combined to win gold in the 4x400m relay and Hayes earned a bronze medal in the individual 400m.

But perhaps the biggest highlight came in the Bahamas, when Hayes clocked 49.91 at April's Chris Brown Invitational, finishing second only to Shaunae Miller (now Miller-Uibo), the eventual Olympic champion in Rio later that summer.

Now, Hayes had finally caught the attention of a shoe sponsor: Nike, who signed her with the upcoming Olympic Games in mind.

But as the U.S. Olympic Trials approached, Hayes' recurring stress fractures -- an issue since her freshman year of college -- returned. Even still, she clawed her way to the Olympic Trials final and placed eighth in 51.8, nearly a full two seconds slower than her PR.

"I'm a strong believer that everything happens for a reason," she tells me.

Hayes was more cautious in her approach to the season this year. She hadn't raced in more than two months when she stepped foot in Hornet Stadium at Sacramento State in California for the USATF Championships at the end of June.

She executed perfectly to win her first USATF outdoor 400m title this year in 49.72, a new personal best and then a world-leading mark.

Immediately after the race, she approached the media in the mixed zone with hugs and smiles.

"When I got to the last curve, I was like, 'God, this race belongs to you,'" she says. "And I was just able to stay strong and finish real strong and keep my form and not break down."

Quanera Hayes reacts after winning the 2017 USATF 400m title:

The glittering moment was a long time in the making for Hayes, who, despite consistent injuries, had managed to achieve global success during the past two indoor seasons.

The same could not be said for Windle, whom few had picked to make the final, let alone the world team.

A series of non-running-related health issues and ill-timed injuries left many of the Brooks Beasts at less than full health heading into Sacramento, which meant that the 25-year-old was the only athlete of Mackey's group to make a final at USAs. It would be the first U.S. final of his young career, as he had been eliminated in the semis or prelims the past three years.

Pre-race favorite Clayton Murphy, the 2016 Olympic bronze medalist, unexpectedly withdrew from just before the start due to sustained injury from attempting to double in the 1500m.

One of the supposed guaranteed spots to the world team was now up for grabs.

Veteran Erik Sowinski brought the field through 400m in 51.32 with NCAA record holder Donavan Brazier on his tail and 2016 Olympian Charles Jock in third, followed by a gap to the rest of the field and another small gap to the runner in last place: Windle.

But over the final 200m, a meteoric kick launched him to what had only moments earlier seemed like a completely improbable third place.

Drew Windle speaks to media in the mixed zone after making his first world team:

The kid who had never broken 1:45 before this season ran 1:44.95 in the final, and went on to crack 1:45 two more times: a win and PB 1:44.63 at the Track Town Summer Series in New York, and a 1:44.72 fourth-place showing at the Monaco Diamond League -- his first race abroad, where he actually tied with eventual world champion Pierre-Ambroise Bosse of France.

Both Hayes and Windle were cautiously measured about their World Championships chances when we spoke by phone three weeks before their departure.

"I want to win but only one person can win," Hayes said. "I'm just putting it in God's hands and trusting that whatever happens is meant to happen and I'm going to come out healthy."

She won her preliminary round in London, but was the first athlete to miss qualifying for the 400m final. A conservative start in her semi-final left her just shy of contention with the top two automatic qualifiers, despite closing well on the homestretch.

"Of course my execution could have been better," she said to USATF after the race. "I backed off a little bit on the back stretch, but as you could see I had a lot left to fight in the end, they were getting away from me. I almost caught up to her and got second place, but I'm happy. I'm not disappointed at all. I gave it my best. It was just execution, not because of my fitness or anything else. My execution was a little off today."

Windle approached London with the same "survive and advance" attitude as Sacramento. He ultimately finished three places outside of qualifying to the final; no Americans advanced to the medal round.

"It's just a high level of racing," he said to USATF after the semi-final race. "Everybody here is really good. I just didn't quite have it in my legs this weekend. It's disappointing, but I have nothing to hang my head about. I had a phenomenal year. Making the semifinal will pay off down the road in other big championships."

"It's just a high level of racing," he said to USATF after the semi-final race. "Everybody here is really good. I just didn't quite have it in my legs this weekend. It's disappointing, but I have nothing to hang my head about. I had a phenomenal year. Making the semifinal will pay off down the road in other big championships."

Hayes has more chance to contribute to Team USA's medal tally this weekend, as she is a likely pick to race in either the 4x400m relay prelims or final, or both rounds.

After all, despite tactical errors in her 400m rounds, Hayes is the second-fastest woman in the world this year. And that's a fact neither helped nor hindered by her enrollment in an NCAA Division II program.

"I wouldn't change anything about competing for Division II," she says definitively at the end of our conversation. "You can't put a division on speed."

That was the question I got after an hour of chatting with Quanera Hayes -- the reigning U.S. champion in the 400 meters, bronze medalist in the 2016 World Indoor Championships, American record holder for 300m, and a member of the American contingent at this summer's IAAF World Championships in London.

We sat on yellow chairs in the pristine white marble lobby of the Breezes Resort & Spa in Nassau, Bahamas, one of the designated athlete hotels for the IAAF World Relays this past April. Hayes was there as a member of the Team USA 4x400 relay that would win gold later that weekend.

She asked me why I didn't go pro when I told her I was a former collegiate middle distance runner. Even after I explained how far off my times were from making the NCAA regionals -- much less the USATF Championships -- she laughed it off. Hayes seemed to suggest that deciding to go pro was just that -- a decision, available to anyone with enough devotion to the craft.

That kind of resolve might have been what brought her to London.

Out of 136 Americans named to the world team, 127 competed for NCAA Division I universities. Of the qualifiers, 14 started in the junior or community college ranks before jumping up to Division I. The qualifiers who competed in Division II and NAIA are almost exclusively race walkers or field athletes.

Hayes is an exception. Another is middle distance runner Drew Windle, who was one of the biggest surprises of the U.S. Championships with his third-place, come-from-behind finish in the men's 800m.

Neither Hayes nor Windle made the world final in their respective event, but both athletes navigated well through the first two rounds in London. Hayes' medal hopes are still alive, as she will likely race on Team USA's 4x400m relay in the prelims on Saturday morning. The finals will close out the 2017 competition on Sunday evening.

THE ROAD TO DIVISION II

"I feel like I always knew I was gonna go pro in a sport," Windle tells me over the phone. "But I always imagined I would be playing for the Green Bay Packers."

When Windle was a senior in high school, he stood at 6-foot-3 and weighed 20 pounds heavier than his current 165. He wanted to play tight end, and was considering the football programs at Ashland University and Tiffin University -- two Division II schools in Ohio -- when Trent Mack, Ashland's distance coach, saw some footage of Windle running the 200m in a relay.

When Mack describes Windle, he describes every coach's dream: a "competitive" and "grinding" bundle of raw hunger.

He wanted Windle for the track -- not the (football) field.

He wanted Windle for the track -- not the (football) field. As Windle came around to the idea of focusing on track during his senior year in high school, his time in the 800m dropped dramatically: from a pedestrian 1:57 to a personal best of 1:51.94 at the Ohio state championship to win his one and only state title.

People noticed. And it wasn't just Mack -- who had convinced the burgeoning star to forego football and focus solely on track.

"I heard there were some bigger schools interested in me after the state meet," Windle says. "[But] I talked to the coach at Ashland and my parents and I thought I already had a pretty good thing established. 'Let's stick it out' . . . that was my gut decision."

For Windle, it was about commitment. He resisted the overtures of Division I schools and made the choice to stand by his pledge to Ashland.

"I think he brought it up before I did," Mack remembers. "He told me, 'I want to reassure you that I'm happy with my decision.'"

Like Windle, Hayes flew under the radar her senior year of high school. She ran the 400m and 200m with consistent times around 60 and 25 seconds, respectively.

Justin Davis, the head coach at Livingstone College in Salisbury, North Carolina, first noticed Hayes while attending a local high school meet to scout potential recruits.

"I wasn't looking for anything in particular," he says. "But when I saw her race that day, she won both of her events with pretty fast hand times and was winning pretty significantly. . . [but] wasn't on a lot of people's radars."

"I wasn't looking for anything in particular," he says. "But when I saw her race that day, she won both of her events with pretty fast hand times and was winning pretty significantly. . . [but] wasn't on a lot of people's radars."Like Windle, Hayes was verbally committed to Livingstone at the North Carolina state meet before blowing out her personal best with a 56.46 in the 400m, the fastest of any athlete in the prelims.

Although she placed fourth in the final with a 58.06 effort -- she was drained after anchoring her second-place 4x200m relay -- her drop in time caught the eyes of bigger schools. Hayes considered NC State, North Carolina A&T, UNC Greensboro, and UNC Charlotte.

Livingstone, however, remained the most desirable choice for Hayes because of academic standards. Division II universities can be more forgiving when it comes to academic requirements for admission, and Hayes was short a math credit. Livingstone was the only school that still offered her a partial scholarship even though she would have to take an academic redshirt.

"That was the best decision," Hayes says. "My plan was to get a scholarship . . . they were the only school who would give me a scholarship even though I would have to sit out."

Hayes would eventually become one of the most decorated athletes in Livingstone's history.

"By the grace of God we were able to get her," Davis says. "Sometimes DII is a strange area. . . you either choose DII or it chooses you."

CREATING A LEGACY

When Hayes won her first national title as a redshirt sophomore, she crossed the line in 51.54.

She had never broken 53 seconds before that race.

Not only was she Livingstone's first female NCAA champion, but she would eventually become the first woman from any Division II school to win three consecutive NCAA outdoor 400m titles.

"That was crazy for me," Hayes remembers. "I was so shocked. I don't know. . . I had never won anything big in my entire life. I never won a state championship. I finally felt that I had accomplished something that I've been waiting for for a very long time."

Her coach was shocked, too.

"I was a pretty young coach at the time," Davis says. "When she crossed the line and I saw that time, my body went numb. To be the head coach and to experience my first national champion and a time that matched up with any athlete in the nation . . . it was just amazing."

Hayes' time would have made her an All-American at the Division I Championship and many bigger schools took note.

"A lot of [DI] coaches came to me," she says. "I actually wanted to go to the University of South Carolina. It was very overwhelming."

She had old friends at South Carolina, and Hayes thought seriously about joining them in Columbia, but her mother and coaches encouraged her to stay with Livingstone's small setting in Salisbury to keep on track with her academics.

She had old friends at South Carolina, and Hayes thought seriously about joining them in Columbia, but her mother and coaches encouraged her to stay with Livingstone's small setting in Salisbury to keep on track with her academics. "That's what the Division II model is about: balancing academics and athletics," Davis says.

By her junior year, Hayes had formed a tight-knit community between her track teammates and her sorority, Alpha Kappa Alpha, which made it easier to accept the decision.

"Those are my sisters," she says of her AKA friends. "I would've had to start over at another school. That's why it wasn't as hard and I wasn't as upset to stay. I did have a whole life at Livingstone."

Ultimately, she feels it was the right decision.

"I still got my education," she says. "I was still able to compete. I was still able to go pro. I had everything I really needed. . . I wasn't another number in my division, in my conference. I had a name for myself."

Windle's 2013 NCAA Indoor 800m title was the first of his six consecutive NCAA Championship wins in the distance. He also helped the Eagles win national titles in the 4x400m relay and distance medley relay.

Mack, his coach, points to a comical moment at the NCAAs during Windle's freshman year as the catalyst for his future success.

Mack, his coach, points to a comical moment at the NCAAs during Windle's freshman year as the catalyst for his future success."He'll kill me for saying this," Mack says. "But with two laps to go to in the prelims at the indoor national meet as a freshman, he makes a pretty strong move and gaps the field a little bit. He held the move and I was like, 'What is he doing?' I'm starting to worry here, he runs about half a lap pretty aggressively and settles back in and the field catches back up and I'm like, 'Oh my goodness, what is going on?' He finished and just made the finals. He came up to me afterwards with a little smirk on his face and he's like, 'I miscounted the laps!'"

Windle took sixth in 1:54.03 -- his first of 10 All-American honors.

Windle wanted to break 1:50 his freshman year, a goal Mack deemphasized in favor of honing race tactics.

"We talked about not putting so much focus the first year on time, but learning how to race at the championship level," Mack says. "He didn't break 1:50 as a freshman but he ran 1:50 three times, and that was a big factor setting him up for his second year, where I think he skipped 1:49 altogether."

At the 2013 NCAA DII Indoor Championships, Windle ran 1:50 in the prelims and 1:48.75 in the final to win by two full seconds for his first national title. He repeated the feat at outdoor nationals, and, once again -- like his breakthrough performance at the Ohio state meet -- questions arose of whether or not Windle would ditch his DII program for a DI school.

"When I won my first two titles in the 800m my sophomore year, people were like, 'You should transfer to a bigger DI school and see what you can do there,' but I was happy at Ashland," he says. "Running in Division II made me learn how to be a consistent racer and learn my ideal style of racing a lot quicker."

Both Windle and Mack agree that it can be a pro and a con that DII athletes don't see as much competition.

"The biggest program doesn't mean that's your opportunity to run and compete to the best of your ability," Mack says. "Even thinking about the social environment . . . At times, Drew is very quiet, and I think a smaller campus size was a great fit for him and that's a big part of it that you have to really know about yourself and answer truthfully."

GOING PRO

Windle was sitting in a night class in October of his senior year when he was startled from the doldrums of his English elective by a direct message on Twitter from Brooks Beasts head coach Danny Mackey.

"Somebody was presenting at the front of the class and I just got up and went to the bathroom," Windle remembers. "I just had to collect myself and realize what was happening in that moment."

Windle had lowered his personal best to 1:46 as a junior, and he planned to pursue a professional running career after graduation. He just wasn't sure how.

"I knew that 1:46 from a small school would stick out a little bit, but I didn't really know how the process [of turning pro] worked."

The two continued to chat every few weeks throughout the school year. In the spring, Windle graduated and went up to Oregon to compete at the Portland Track Festival, where he met up with the Beasts' Cas Loxsom. The two drove to Seattle together -- where the Beasts are headquartered -- and Windle spent about a week and a half with the team before USAs.

FloTrack interviewed Windle after he won his sixth straight NCAA Division II 800m title:

Mackey says he first took note of Windle at the 2014 USATF Championships from a story that Loxsom told him. The kid who nobody had heard of from the school nobody had heard of ran the fourth-fastest time in the prelims to make the semifinal, but he did it while racing in full tights because he had forgotten his shorts. And as if that wasn't enough, the kid had accidentally walked three miles to the stadium before the event because he didn't know how far away it was from his hotel.

"I really liked two things," Mackey says. "One, he seemed very level-headed and positive from the conversations I had with him, and, two, from a racing standpoint, even though he was Division II, he seemed like a very quiet competitor--someone I could easily work with who would be a strong addition to the team who had a big way of improving."

He believes the DII roots gave Windle grit and gratitude.

"At Division II schools, you don't really get anything," Mackey says. "You don't get shoes, you a get a shitty kit, your travel budget sucks. I have worked with some athletes that are entitled and feel like nothing is good enough. The grass is always greener. He's got a lot of humility.

"On the racing side of things, he's learned how to win. That's an abstract trait and maybe he was just better than everybody else and didn't have to work as hard, but if you look at his races, he knows how to win."

Nick Symmonds, a former Brooks Beast who retired from the sport this year, echoes Mackey's sentiment.

The 2013 world silver medalist would know, as he is also a product of a non-Division I program, having won seven NCAA titles at Willamette University, a Division III institution.

"[Head coach] Kelly Sullivan, when he brought me to Williamette, he said, 'You're gonna be the best athlete in every race and probably best athlete in DIII and you need to develop a taste for winning," Symmonds says. "You need to be able to win slow races, fast races, win when you get bumped, win when you get elbowed, win when you trip.' And I never lost in my collegiate running career.

"I took that winning mentality, that addiction to winning, with me when I became a pro. You see that same thing in Drew: he's won [lots of DII titles] and had a taste for winning. If you go to DI and you never win a race and you're always fighting for third or fourth, you're not addicted to winning. You start to settle, 'Oh, I'm a mid-packer,' and you think that's ok. You don't understand what it means to be a winner."

Drew Windle finally got to race Brooks Beasts mentor Nick Symmonds in the preliminary round of the 800m at USAs this year:

Hayes was more relevant on the U.S. senior level right away, as she placed fifth in the USATF final a few weeks after her college graduation.

"The only people to beat her were former Olympians and world champions," her agent, Charles Wells of Trident Sports Management, says now. "We definitely had something real awesome on our hands."

Wells is a former Division II athlete himself and was actually teammates at Texas A&M - Kingsville with high jumper Jeron Robinson, one of the few DII products to represent Team USA at the World Championships this year. His background gave him added interest in Hayes and he signed her immediately following graduation.

But it still took her nearly a year to pick up a shoe sponsor.

Hayes moved to Clermont, Florida, as she had always told herself she would only turn pro if she moved to the Sunshine State. She didn't join one of Clermont's training groups, though. She took direction from Derrick White of Life Speed Athletics, but preferred to train on her own.

"It was hard, very hard," she says of her year training without a sponsor. "I was training full-time. Nobody wanted me to get a job, I tried to but my mom and my coach at the time kept saying, 'No, just wait, it'll happen.' I just kept working hard and I knew it would come eventually if I could stay focused."

She was also alone in Florida, 600 miles away from everyone she'd ever known. Thanksgiving was particularly hard, and she broke down in tears at practice after her mom -- who was briefly visiting -- left to go back home for the holiday. Her coach was also away on vacation with family and his friend was at the track to help her with the workout, though he ended up helping in a different way by giving her the phone number of a girl he knew -- Chelsea -- who was Hayes' age. Now, she had an ally.

"She's one of my best friends now," Hayes says. "I explain a lot of stuff to her about what I go through and what I do as a professional track and field athlete because she didn't know anything about that. All she really knows is that I'm a professional athlete and run really fast and she knows I run a 400m."

The struggle through the fall yielded massive gains in the spring, as Hayes won the USATF Indoor National Championship in the 400m and qualified to represent Team USA at the IAAF World Indoor Championships in Portland, Oregon.

Quanera Hayes speaks to the media after winning the 2016 USATF Indoor Championships 400m:

At World Indoors, he quartet of Hayes, Natasha Hastings, Courtney Okolo, and Ashley Spencer combined to win gold in the 4x400m relay and Hayes earned a bronze medal in the individual 400m.

But perhaps the biggest highlight came in the Bahamas, when Hayes clocked 49.91 at April's Chris Brown Invitational, finishing second only to Shaunae Miller (now Miller-Uibo), the eventual Olympic champion in Rio later that summer.

Now, Hayes had finally caught the attention of a shoe sponsor: Nike, who signed her with the upcoming Olympic Games in mind.

But as the U.S. Olympic Trials approached, Hayes' recurring stress fractures -- an issue since her freshman year of college -- returned. Even still, she clawed her way to the Olympic Trials final and placed eighth in 51.8, nearly a full two seconds slower than her PR.

"I'm a strong believer that everything happens for a reason," she tells me.

MAKING THE WORLD TEAM

Hayes was more cautious in her approach to the season this year. She hadn't raced in more than two months when she stepped foot in Hornet Stadium at Sacramento State in California for the USATF Championships at the end of June.

She executed perfectly to win her first USATF outdoor 400m title this year in 49.72, a new personal best and then a world-leading mark.

Immediately after the race, she approached the media in the mixed zone with hugs and smiles.

"When I got to the last curve, I was like, 'God, this race belongs to you,'" she says. "And I was just able to stay strong and finish real strong and keep my form and not break down."

Quanera Hayes reacts after winning the 2017 USATF 400m title:

The glittering moment was a long time in the making for Hayes, who, despite consistent injuries, had managed to achieve global success during the past two indoor seasons.

The same could not be said for Windle, whom few had picked to make the final, let alone the world team.

A series of non-running-related health issues and ill-timed injuries left many of the Brooks Beasts at less than full health heading into Sacramento, which meant that the 25-year-old was the only athlete of Mackey's group to make a final at USAs. It would be the first U.S. final of his young career, as he had been eliminated in the semis or prelims the past three years.

Pre-race favorite Clayton Murphy, the 2016 Olympic bronze medalist, unexpectedly withdrew from just before the start due to sustained injury from attempting to double in the 1500m.

One of the supposed guaranteed spots to the world team was now up for grabs.

Veteran Erik Sowinski brought the field through 400m in 51.32 with NCAA record holder Donavan Brazier on his tail and 2016 Olympian Charles Jock in third, followed by a gap to the rest of the field and another small gap to the runner in last place: Windle.

But over the final 200m, a meteoric kick launched him to what had only moments earlier seemed like a completely improbable third place.

Drew Windle speaks to media in the mixed zone after making his first world team:

The kid who had never broken 1:45 before this season ran 1:44.95 in the final, and went on to crack 1:45 two more times: a win and PB 1:44.63 at the Track Town Summer Series in New York, and a 1:44.72 fourth-place showing at the Monaco Diamond League -- his first race abroad, where he actually tied with eventual world champion Pierre-Ambroise Bosse of France.

Both Hayes and Windle were cautiously measured about their World Championships chances when we spoke by phone three weeks before their departure.

"I want to win but only one person can win," Hayes said. "I'm just putting it in God's hands and trusting that whatever happens is meant to happen and I'm going to come out healthy."

She won her preliminary round in London, but was the first athlete to miss qualifying for the 400m final. A conservative start in her semi-final left her just shy of contention with the top two automatic qualifiers, despite closing well on the homestretch.

"Of course my execution could have been better," she said to USATF after the race. "I backed off a little bit on the back stretch, but as you could see I had a lot left to fight in the end, they were getting away from me. I almost caught up to her and got second place, but I'm happy. I'm not disappointed at all. I gave it my best. It was just execution, not because of my fitness or anything else. My execution was a little off today."

Windle approached London with the same "survive and advance" attitude as Sacramento. He ultimately finished three places outside of qualifying to the final; no Americans advanced to the medal round.

"It's just a high level of racing," he said to USATF after the semi-final race. "Everybody here is really good. I just didn't quite have it in my legs this weekend. It's disappointing, but I have nothing to hang my head about. I had a phenomenal year. Making the semifinal will pay off down the road in other big championships."

"It's just a high level of racing," he said to USATF after the semi-final race. "Everybody here is really good. I just didn't quite have it in my legs this weekend. It's disappointing, but I have nothing to hang my head about. I had a phenomenal year. Making the semifinal will pay off down the road in other big championships."Hayes has more chance to contribute to Team USA's medal tally this weekend, as she is a likely pick to race in either the 4x400m relay prelims or final, or both rounds.

After all, despite tactical errors in her 400m rounds, Hayes is the second-fastest woman in the world this year. And that's a fact neither helped nor hindered by her enrollment in an NCAA Division II program.

"I wouldn't change anything about competing for Division II," she says definitively at the end of our conversation. "You can't put a division on speed."