Outdoor Track and Field on Flotrack 2013Jul 24, 2013 by Garrett Reim

To make it to the next level, strength training is a must

To make it to the next level, strength training is a must

In May, the Nike Oregon Project completed a five-day stint of altitude training in Park City, Utah. Flotrack was there to capture it all. Though the Oregon Project was focused on using the thin alpine air to stress and build their aerobic capacity, as always, coach Alberto Salazar's group was training much more.

The pictures below shows that the group also maintained an intense strength training regimen. Strength training has become a more and more important focus of elite distance running. Because of its ability to boost performance, Salazar’s group is setting time aside for running specific strength training - often lifting heavy weights with limited repititons - to perfect their form.

Human Racecars

To understand why strength training betters running form it is helpful to think of running form as a chassis on a race car. For example, Formula 1 racecars hold themselves together by being built of lightweight and super-strong carbon fiber frames that hold form even at maximum speeds around 215 mph and forces five times the weight of gravity.

By rigidly holding their form, F1 racecars efficiently move energy from their engine through wheels into forward motion. Without such strength, F1 racecars would lose power and speed to flex in their frames and wobble in their misaligned wheels. A strong chassis is key to F1 racecar’s performance.

Similar to a racecar’s chassis, good running form also translates power into efficient forward motion. Running with good biomechanics transfer most of your effort into forward motion. Running with a wobbly axle (see hips) or sagging frame (see core) wastes forward motion and energy is lost in excess body movement. Having the strength to maintain good form makes a huge difference in forward momentum.

Several energy systems, not mutually exclusive

For the most of a distance race, the aerobic system’s low-power / long endurance capabilities meet the demands of competition. And traditionally, when it came to strength, distance runners have taken a light approach - training with sit-ups and other high repetition conditioning exercises. However, runners are discovering moments, especially at the end of the race, when the pace accelerates or when their aerobic abilities fatigue. They need energy delivered in a powerful snap.

The Body’s Energy Systems

Aerobic System

Aerobic power, the kind that propels distance runners through most of their race, is a low power / long endurance sort of energy system. It is fueled by a combination of oxygen and sugar / fat (glycogen or lipids). The aerobic system can take you far, but not fast.

Anaerobic System

The body’s energy system which generates energy without oxygen has two parts: the Anaerobic Glycolytic system and the ATP-PC system.

Glycolytic System

Provides the body powerful strength endurance for between 10 seconds to 2 minutes. Think the 800m, or 50+ sit-ups.

ATP-PC system

Delivers explosive, short term power. Think powerlifting, or sprinting for around 8-10 seconds.

The strength to hold it all together: ATP-PC system

The ATP-PC system is primarily trained by lifting heavy weights. It's the perfect backup for when the body’s other energy systems just won’t cut it. When a runner must suddenly accelerate or needs an additional strength boost to hold their running form together, the ATP-PC system delivers the power needed.

With the Nike Oregon Project, it is typical to see Mo Farah or Galen Rupp working their ATP-PC systems by doing Olympic lifts. Olympic lifting is fundamentally the practice of standing up straight against the weight of a heavy barbell. For runners, Olympic lifting trains the body to maintain upright form against the fatigue and forces of racing. When your aerobic capacity and strength endurance (Anaerobic Glycolytic system) can no longer hold your form, the strength developed from high weight / low repetition activities like Olympic lifting keeps it all together.

Galen Rupp Weight Room Workout Video

What’s more, coach Salazar has tailored the exercises specific to running by modifying the Olympic Lifts to mimic running form. This gives the athletes the added benefit of specificity. He explains, "This is as important as anything we do in our training. It isn’t just, ‘Well lets just go hit the weight room and do a few exercises.’ This is a very sort of synchronized and specific training program that they are on."

Rupp performs a modified squat, which is designed to mimic and strengthen good running form.

A lost art

While strength training is fashionable lately, Salazar’s Nike Oregon Project certainty isn’t the first to pioneer the concept.

Nearly three decades before Salazar, Peter Coe, the coach and father of famed Sebastian Coe, used strength training to develop strong and efficient form and to prevent injury in his athletes. He explained that strength training benefited his athletes by "minimizing stress on the connective tissues of the musculoskeletal system (ligaments, tendons, and cartilage)" and making "the entire support system more durable.”

An engineer by training, Peter Coe’s approach was always methodical and technical. In his all-encompassing book Better Training for Distance Runners, you can see his thinking first hand.

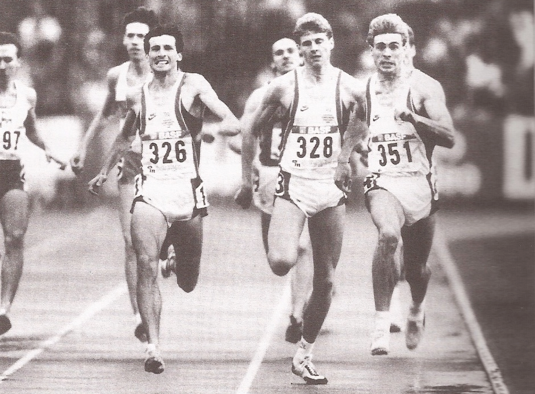

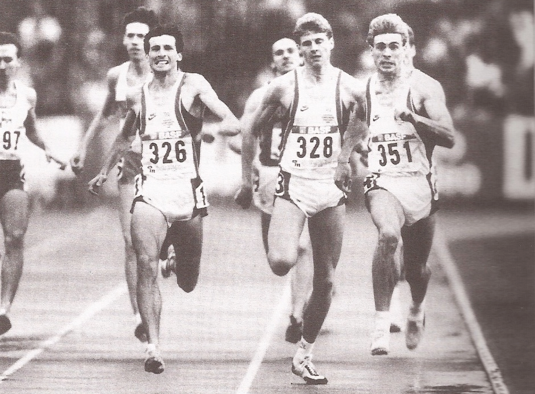

Observing the photograph below, Peter Coe noted that even the powerful engine of Steve Cram (former 1500m world record holder and '84 1500m Olympic silver medalist), was poorly served by his misaligned gait and could benefit from improved biomechanics.

Photo from the '86 European Championships

"Lower-limb running mechanics in three of Britain’s best 1500m runners. Note the optimal foot orientation parallel to the path of movement in Seb Coe (326) and Tom McKean (351), but excessive lower-limb rotation in Steve Cram (328)," observed Coe.

You can almost imagine Peter Coe perfectly placed in a Formula 1 pit crew. He would go onto describe the seriousness of poor biomechanics that burdened even the great Steve Cram.

Steve Cram’s left foot “is markedly turned out (everted), as well as his left knee, giving that leg a reduced forward vector as it generates propulsive thrust," said Coe. "An excessive amount of Cram’s propulsive energy is being absorbed by the knee and ankle joints in resisting the torsional stresses generated by his everted foot plant."

"This style of foot planting not only increases the risk of lower-limb injuries, but also reduces his stride length by more than 1 cm. At his race pace and stride length in Stuttgart ('86 European Championships) Cram was losing a little more than 50 cm for every 100m of distance covered. In today’s races, this is an enormous disadvantage to overcome."

Steve Cram lost the '86 800m European Championships by 0.33 seconds to Sebastian Coe. Cram finished in 1:44.88, which was good for third place while Sebastian Coe took the win in 1:44.50. That margin could have been the made up in the 50cm Steve Cram was losing every 100m due to poor biomechanics.

Coach Coe goes on to speculate, “It might also be of interest that over several of his competitive years, Steve Cram was bothered by lower-limb running injuries, particularly to his calf muscles.” Injuries probably caused by his poor mechanics.

Loose biomechanics can put a lot of stress on the body’s joints, ligaments and muscles - stress that in time can cause injury. The body may in time beat on itself until breakdown, much like a car with a bent wheel axle.

The margins still matter

As was the case in the '86 European Championships, the importance of winning the margins remains paramount today. Take for example the 2012 10,000m Olympic final. The difference between Mo Farah’s first place and Galen Rupp’s second, was 0.9 seconds. Over those 25 laps, 0.9 second seconds is equal to 0.055% of Farah’s race. If he ran 0.056% slower, he could have lost the Olympic title. Better biomechanics may have made this difference.

This is why having excellent biomechanics matters so much and Salazar knows it. "I believe this[strength training] has a very direct correlation to speed development, and endurance, and strength," says Salazar. He elaborates, "this is how you create runners that have great biomechanics, and are able to hold those great biomechanics throughout the whole 10,000 meter race, and be able to sprint at the end."

Mo Farah powers away from the field

Powerful strength training but not just with weights

What’s more, the Nike Oregon Project is known to incorporate a number of alternative strength exercises, such as bounding. In a recent Inside Nike Training Video, Salazar breaks down the benefits of bounding by saying, "This is a sort of weight training, to get your legs stronger but doing it in a running specific manner, so it’s going to have the greatest carry over to improving your stride length and your power with each stride." Again, the Nike Oregon Project is focusing on strength training to improve stride mechanics and power.

Inside Nike: Bounding

Strength training has been long dormant, but why?

Though Peter Coe championed strength training 30 years ago and Salazar is helping to make it popular again, for many years weight training was thought to be detrimental. Ever mindful of their mass, runners avoided weights fearing the possibility of bulking up. Salazar takes this fear head on and dismisses it. "It’s very hard to bulk up. I’ve never seen a single athlete of mine bulk up."

"Bulking up not only means lifting really hard but eating a ton, and it’s very hard to gain weight. Not even a single one of my athletes have gained 2lbs. The only one’s that have gained a little bit of weight have been the girls… because they haven’t been as muscularly toned… but it’s good functional muscle that actually allows them to compete better."

In fact, Salazar emphatically states weight training is needed to make it to the next level. “Back going thirty years ago there was an old philosophy about strength training for distance runners. It was this idea of lightweights and lots of reps. And I really don’t believe in that. When do something like that, at some point there’s no stimulus or further growth. At some point if you’re just doing lots of reps and light weights, you’re going to maintain where you are at but you’re not going grow,” he says.

To make it to the next level strength training is a must.

The pictures below shows that the group also maintained an intense strength training regimen. Strength training has become a more and more important focus of elite distance running. Because of its ability to boost performance, Salazar’s group is setting time aside for running specific strength training - often lifting heavy weights with limited repititons - to perfect their form.

Human Racecars

To understand why strength training betters running form it is helpful to think of running form as a chassis on a race car. For example, Formula 1 racecars hold themselves together by being built of lightweight and super-strong carbon fiber frames that hold form even at maximum speeds around 215 mph and forces five times the weight of gravity.

By rigidly holding their form, F1 racecars efficiently move energy from their engine through wheels into forward motion. Without such strength, F1 racecars would lose power and speed to flex in their frames and wobble in their misaligned wheels. A strong chassis is key to F1 racecar’s performance.

Similar to a racecar’s chassis, good running form also translates power into efficient forward motion. Running with good biomechanics transfer most of your effort into forward motion. Running with a wobbly axle (see hips) or sagging frame (see core) wastes forward motion and energy is lost in excess body movement. Having the strength to maintain good form makes a huge difference in forward momentum.

Several energy systems, not mutually exclusive

For the most of a distance race, the aerobic system’s low-power / long endurance capabilities meet the demands of competition. And traditionally, when it came to strength, distance runners have taken a light approach - training with sit-ups and other high repetition conditioning exercises. However, runners are discovering moments, especially at the end of the race, when the pace accelerates or when their aerobic abilities fatigue. They need energy delivered in a powerful snap.

The Body’s Energy Systems

Aerobic System

Aerobic power, the kind that propels distance runners through most of their race, is a low power / long endurance sort of energy system. It is fueled by a combination of oxygen and sugar / fat (glycogen or lipids). The aerobic system can take you far, but not fast.

Anaerobic System

The body’s energy system which generates energy without oxygen has two parts: the Anaerobic Glycolytic system and the ATP-PC system.

Glycolytic System

Provides the body powerful strength endurance for between 10 seconds to 2 minutes. Think the 800m, or 50+ sit-ups.

ATP-PC system

Delivers explosive, short term power. Think powerlifting, or sprinting for around 8-10 seconds.

| Energy Systems | Maximum Power Duration | Where it works (examples) |

| ATP-PC | 8 - 10 seconds | Power lifting, sprinting |

| Anaerobic Glycolytic | 10 seconds - 2 minutes | Sit-ups, 800m |

| Aerobic | 2 minutes and beyond | 5k, 10k, and beyond |

The strength to hold it all together: ATP-PC system

The ATP-PC system is primarily trained by lifting heavy weights. It's the perfect backup for when the body’s other energy systems just won’t cut it. When a runner must suddenly accelerate or needs an additional strength boost to hold their running form together, the ATP-PC system delivers the power needed.

With the Nike Oregon Project, it is typical to see Mo Farah or Galen Rupp working their ATP-PC systems by doing Olympic lifts. Olympic lifting is fundamentally the practice of standing up straight against the weight of a heavy barbell. For runners, Olympic lifting trains the body to maintain upright form against the fatigue and forces of racing. When your aerobic capacity and strength endurance (Anaerobic Glycolytic system) can no longer hold your form, the strength developed from high weight / low repetition activities like Olympic lifting keeps it all together.

Galen Rupp Weight Room Workout Video

What’s more, coach Salazar has tailored the exercises specific to running by modifying the Olympic Lifts to mimic running form. This gives the athletes the added benefit of specificity. He explains, "This is as important as anything we do in our training. It isn’t just, ‘Well lets just go hit the weight room and do a few exercises.’ This is a very sort of synchronized and specific training program that they are on."

Rupp performs a modified squat, which is designed to mimic and strengthen good running form.

A lost art

While strength training is fashionable lately, Salazar’s Nike Oregon Project certainty isn’t the first to pioneer the concept.

Nearly three decades before Salazar, Peter Coe, the coach and father of famed Sebastian Coe, used strength training to develop strong and efficient form and to prevent injury in his athletes. He explained that strength training benefited his athletes by "minimizing stress on the connective tissues of the musculoskeletal system (ligaments, tendons, and cartilage)" and making "the entire support system more durable.”

An engineer by training, Peter Coe’s approach was always methodical and technical. In his all-encompassing book Better Training for Distance Runners, you can see his thinking first hand.

Observing the photograph below, Peter Coe noted that even the powerful engine of Steve Cram (former 1500m world record holder and '84 1500m Olympic silver medalist), was poorly served by his misaligned gait and could benefit from improved biomechanics.

Photo from the '86 European Championships

"Lower-limb running mechanics in three of Britain’s best 1500m runners. Note the optimal foot orientation parallel to the path of movement in Seb Coe (326) and Tom McKean (351), but excessive lower-limb rotation in Steve Cram (328)," observed Coe.

You can almost imagine Peter Coe perfectly placed in a Formula 1 pit crew. He would go onto describe the seriousness of poor biomechanics that burdened even the great Steve Cram.

Steve Cram’s left foot “is markedly turned out (everted), as well as his left knee, giving that leg a reduced forward vector as it generates propulsive thrust," said Coe. "An excessive amount of Cram’s propulsive energy is being absorbed by the knee and ankle joints in resisting the torsional stresses generated by his everted foot plant."

"This style of foot planting not only increases the risk of lower-limb injuries, but also reduces his stride length by more than 1 cm. At his race pace and stride length in Stuttgart ('86 European Championships) Cram was losing a little more than 50 cm for every 100m of distance covered. In today’s races, this is an enormous disadvantage to overcome."

Steve Cram lost the '86 800m European Championships by 0.33 seconds to Sebastian Coe. Cram finished in 1:44.88, which was good for third place while Sebastian Coe took the win in 1:44.50. That margin could have been the made up in the 50cm Steve Cram was losing every 100m due to poor biomechanics.

Coach Coe goes on to speculate, “It might also be of interest that over several of his competitive years, Steve Cram was bothered by lower-limb running injuries, particularly to his calf muscles.” Injuries probably caused by his poor mechanics.

Loose biomechanics can put a lot of stress on the body’s joints, ligaments and muscles - stress that in time can cause injury. The body may in time beat on itself until breakdown, much like a car with a bent wheel axle.

The margins still matter

As was the case in the '86 European Championships, the importance of winning the margins remains paramount today. Take for example the 2012 10,000m Olympic final. The difference between Mo Farah’s first place and Galen Rupp’s second, was 0.9 seconds. Over those 25 laps, 0.9 second seconds is equal to 0.055% of Farah’s race. If he ran 0.056% slower, he could have lost the Olympic title. Better biomechanics may have made this difference.

This is why having excellent biomechanics matters so much and Salazar knows it. "I believe this[strength training] has a very direct correlation to speed development, and endurance, and strength," says Salazar. He elaborates, "this is how you create runners that have great biomechanics, and are able to hold those great biomechanics throughout the whole 10,000 meter race, and be able to sprint at the end."

Mo Farah powers away from the field

| Rank | Name | Nationality | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Mo Farah |

|

27:30.42 |

|

|

|

Galen Rupp |

|

27:30.90 |

|

|

|

Tariku Bekele |

|

27:31.43 |

|

| 4 | Kenenisa Bekele |

|

27:32.44 |

|

| 5 | Bedan Karoki Muchiri |

|

27:32.94 |

|

| 6 | Zersenay Tadese |

|

27:33.51 |

|

| 7 | Teklemariam Medhin |

|

27:34.76 |

|

| 8 | Gebregziabher Gebremariam |

|

27:36.34 |

|

| 9 | Polat Kemboi Arikan |

|

27:38.81 | PB |

| 10 | Moses Ndiema Kipsiro |

|

27:39.22 |

|

Powerful strength training but not just with weights

What’s more, the Nike Oregon Project is known to incorporate a number of alternative strength exercises, such as bounding. In a recent Inside Nike Training Video, Salazar breaks down the benefits of bounding by saying, "This is a sort of weight training, to get your legs stronger but doing it in a running specific manner, so it’s going to have the greatest carry over to improving your stride length and your power with each stride." Again, the Nike Oregon Project is focusing on strength training to improve stride mechanics and power.

Inside Nike: Bounding

Strength training has been long dormant, but why?

Though Peter Coe championed strength training 30 years ago and Salazar is helping to make it popular again, for many years weight training was thought to be detrimental. Ever mindful of their mass, runners avoided weights fearing the possibility of bulking up. Salazar takes this fear head on and dismisses it. "It’s very hard to bulk up. I’ve never seen a single athlete of mine bulk up."

"Bulking up not only means lifting really hard but eating a ton, and it’s very hard to gain weight. Not even a single one of my athletes have gained 2lbs. The only one’s that have gained a little bit of weight have been the girls… because they haven’t been as muscularly toned… but it’s good functional muscle that actually allows them to compete better."

In fact, Salazar emphatically states weight training is needed to make it to the next level. “Back going thirty years ago there was an old philosophy about strength training for distance runners. It was this idea of lightweights and lots of reps. And I really don’t believe in that. When do something like that, at some point there’s no stimulus or further growth. At some point if you’re just doing lots of reps and light weights, you’re going to maintain where you are at but you’re not going grow,” he says.

To make it to the next level strength training is a must.