Ahmaud Arbery, Race And Running: A Conversation With Alison Desir

Ahmaud Arbery, Race And Running: A Conversation With Alison Desir

Alison Desir, a runner and activist, spoke with FloTrack about the Ahmaud Arbery case, race and running.

Last Friday, professional and recreational runners around the country ran 2.23 miles in honor of Ahmaud Arbery using the hashtag #IRunWithMaud.

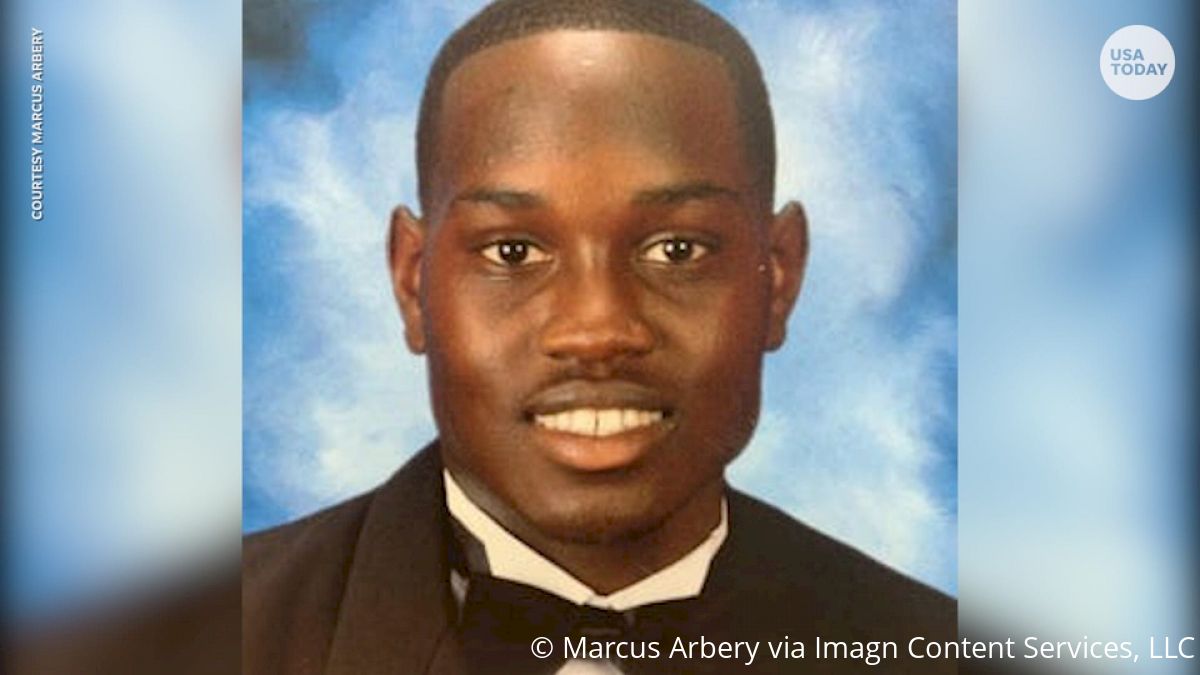

Arbery, a 25-year-old black man, was shot and killed while jogging outside Brunswick, Georgia, after being chased in a truck by two white men with guns. The date of the run, May 8th, would have been Arbery’s 26th birthday and the distance signified his death, February 23rd. On Thursday last week, video surfaced of the shooting. Two days later, Gregory McMichael and his son Travis Michael were charged with murder and aggravated assault.

Also on Friday, Alison Desir wrote a piece for Outside Magazine entitled, “Ahmaud Arbery and Whiteness in the Running World.” Desir is a runner and activist based in New York City. She’s the founder of Harlem Run, Run 4 All Women and Global Womxn Run Collective. FloTrack spoke with her about Arbery’s case, race and running on Friday. The conversation has been edited for clarity and brevity.

What has been the feedback to the Outside Magazine piece?

The response so far has been positive and I think a lot about the emotional investment and the time that I put into the piece and a lot of people are thanking me obviously and are being really gracious that I give suggestions. And for me I think the truth of it is, I am an optimist and that comes a lot now from being a mother, there’s this quote by Zora Neale Hurston….”If you are silent about your (pain), they’ll kill you and say you enjoyed it.”

For me, my son is hopefully is going to live a long and full life and I know I can be a part of making that possible by using my platform. So, is it exhausting? Yes. Is it draining? Yes. Is it emotionally difficult to have these conversations and risk putting yourself out there in that way? Yes. But for me, in this moment, it’s what I feel called to do.

Did you do the run today (Friday)?

Yeah, we got out. At this point, I’m walking because I’m 9.5 months postpartum and there was a part of me that was going to kick ass and get back into shape but COVID-19 and other things humbled me, but we got out for a walk, my husband and my son.

Can you expand on this part of your article? ”For too long, the running community has pretended as though it were possible to keep politics out of running.”

I think within running and within the sports community, there’s sort of this idea as though sports are separate from all of the systems and institutions whether it’s patriarchy or white supremacy, sexism.

At some point, a white reporter said to Lebron James, “shut up and dribble” as though the sports world is immune to this when in fact this quote, I keep quoting people because there’s so many people who came before me and exist now doing this work who don’t get the shine, but ”white supremacy isn’t the shark, it’s the water.” What that means is every single thing that exists is steeped in white supremacy so when you’re talking about running, running exists within a world where white achievement is privileged where those stories are preferenced, where if you are Caster Semenya people feel entitled to look in your pants to tell you whether you can run or not, where if you decide to go jogging at 1 pm in Georgia you can get shot dead and it will take two months for folks to follow up.

Every moment of my life, I’m a black woman. That includes when I’m running outside. So I just think it’s this fallacy and it is really perpetuated by the fact that white people and white men control this industry and every industry. But the personal is political. Everything is political.

I guess I’m fed up at this point and calling it out.

I know you’ve been involved in activism for many years, but prior to this did you see running as an act of resistance or protest?

Yeah, absolutely. For me, I’m a first-generation American. My father passed away but was Haitian, my mother is Columbian so what you learn in school is white history but what I learned at home was the history of the Haitian revolution, I learned about protest movements in the Civil Rights movement and in all of these spaces movement, moving your body was a political act because truth be told when a black or brown person is outside, is daring to be in public in a space where they could be killed, that in and of itself is a political act.

I came to running long distance after going through a period of depression but the roots of it all were knowing that the personal is political and that my moving body is connected to the work of my ancestors who moved publicly to make statements.

Runners speak glowingly about running in a way that describes it as much as a spiritual exercise as a physical one. But I wanted to ask you about two of those elements that often get cited and brought up that might not be inclusive or universal--the first is the idea of running as a method of mental escape, you can go out and run and be alone with your thoughts--can you tell me how you grapple with that concept?

I’m glad you bring that up because it’s something that I, myself, can attest to. For me, I came to running as a space for my mental health. I was going through a period of depression, I saw a black friend of mine who was training for a marathon and I was like, “black people don’t run marathons unless they are east Africans, like who is this guy?” And I started running and it totally transformed me mentally and physically, so that’s the thing. We need to look at this with nuance, right. And no criticism to you, but in the press and in a lot of spaces, people want things that are clear cut. Like, “running clears your mind” or “black and brown people can’t get that mental escape,” it’s not true.

I also run for that mental peace, but there’s also that terror in the back of my mind as a black person knowing that that could be my demise. That’s how we exist in multiple worlds. And I also carry privileges. I have a wealth of education, I grew up first-generation immigrant, but to middle-class parents and so for that, that privilege allows me to insert myself into conversations like this even. There’s just nuance to it. Yes, we feel free and we feel terror.

The other cliche is that running it’s not just a mental escape but a physical escape. Running is the one activity that doesn’t require lots of equipment, doesn’t require a field or a gym. People say it can be done anywhere. How does that idea intersect with what people are reconciling with Ahmaud Arbery’s case?

Not to bring in another cliche but it’s not exactly black or white. Running is a sport that is accessible to most, it still requires some sneakers, it still requires a sense of safety, it requires access to streets that aren’t broken, or over-policed. For some black people, the intersection of race and class, they may live in a place where they can live on beautiful streets but they may also fear for their life because they are one of a few in their neighborhood.

I really do appreciate these questions because it speaks to the complexity of these conversations and why I say that we have to stop removing the politics from running because there’s just so much more to these conversations, each of these identities is present.

I was really impressed, I guess that is the word, by Peter Bromka--and I have to admit I did not know who this man was, but he re-shared what I said and then made a post about the ways in which he feels safe in the world and I was moved to tears because I can’t imagine that level of safety, I mean the man said he trespasses. He runs down roads that are closed, that he knows he’s doing something wrong and does it anyway. I can’t even imagine that level of safety in my life.

Last night I went for a walk at 7 o’clock because my brain was about to explode and I was walking and about halfway through I had sent my husband a text, I was like “fuck, it might be dark when I get home,” I’m like Cinderella trying to make it home. This is a real thing, looking behind my back, making sure that I’m not spending too much (time) on my phone, is it going to be rape…..this is outrageous. I think to myself, imagine if all of the energy that I have, combine all my energy that I put into this and my brilliance, I could be curing cancer. But instead, I’m here worrying about my safety.

What’s the racial breakdown of your running group?

Our group is very diverse, racially, age-wise. The leadership is mostly BIPOC, but the group is focused on urban communities and getting folks like us moving. One of the interesting ways the world works is that you can have mostly black leadership, a message around empowerment around people of color and white people, they feel they belong there. And I’m not speaking specifically about Harlem Run because we do talk about these hard issues and they’ll show up and maybe not say anything, but you have an all-white leadership and we know that’s not a place for us and that just speaks to the dynamics of race.

But with Harlem Run, with Run For All Women, with Global Womxn Run Collective it’s all rooted in spaces that are welcoming and not just welcoming by saying “everybody is welcome” but by putting our money where our mouth is. That means that the messaging, the images that we show, if we’re there for both people who both walk and run it can’t just be a bunch of skinny white men who look like they run four-minute miles. You have to have people of different body sizes so they can say, oh I see myself and that was really my “call out, call in” to publications. We are not seeing ourselves, we are not seeing our humanity, whether we are celebrating great things or there’s a tragedy that’s happened we just don’t see ourselves.

In the lead-up to the Olympic Marathon Trials, I believe the New York Times did an analysis of the qualifiers and looked at a bunch of different data points. One of them was race and I believe only 1% of the qualifiers were black (note: the NY Times looked at women’s qualifiers). What connection, if any, do you draw between the tragedy with the Arbery case and that low number of participants?

Ahmaud really is a modern-day lynching. This is a message, don’t be out on the streets. Because if you’re out on the streets, this could happen to you, so that’s one. But then two, black and brown people historically have not had the freedom to be on the streets and they haven’t had the technology or the knowledge around distance running, and then you don’t see yourself represented in publications. It’s just sort of like this circle that reinforces this idea that this is not a place for you and if it is a place for you then you’ll be one of a few. And there’s obviously a difference between East Africans, their representation, and the representation of us. All of that is connected.

I know activism is challenging during a global pandemic, but do you expect more events around Arbery’s case?

I’m thankful that people are now listening and that this story is getting the attention that it’s getting. But just this morning I woke up and there were two other unarmed black men who were gunned down. They weren’t runners but two other black men who were gunned down. This is part of a long history of this happening and the cure is that we dismantle white supremacy so this is not just a short-term moment. I do fear that this will be a moment.

So, to answer your question, you are asking do I expect more activism during the COVID-19 era, I hope so. But this needs to extend well beyond that because every white person needs to take a look in the mirror and ask themselves how am I complicit with white supremacy, it’s not good enough to be a nice guy. You are a nice guy, but you are in rooms where you and a bunch of white guys are the other people represented and you have power. How can you pull other voices into that room? How can you say, “you know, this doesn’t look right, because we aren’t representative of this country, we are not representative of this community.” So those are the ways and I’ve been recommending two books, White Fragility which really forces white people to confront their identity and white people can have a positive white identity once they separate that identity from white supremacy. And the other one is White Supremacy And Me and this is something that I hope is just the beginning of a conversation within the running community and broader society.

With all the things that are inherent in distance running, you need lots of space, you need to be able to go out of your neighborhood and venture other places, it seems like that is going to draw in direct conflict with the systems of power that you’re talking about. Playing basketball, football or soccer, you can separate yourself in a way. Is this going to be a particularly hard issue because of what makes running, running?

Absolutely, this is something that is not only true in the running world but also in the outdoor industry and there are a lot of folks who are working on diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) in the outdoor world because of just that. You think about going into national parks, going into trails, you are going into these places where we know there is danger and the danger isn’t just tripping and falling, the danger is going in and disappearing.

So that’s why I have issue with the runner safety movement that started recently because it’s not just about texting folks and carrying mase and making sure that our breasts aren’t showing it’s about what are the ways that the folks are complicit in this system are going to help us change the system so that we can be safe. Anything that takes place in the outdoors, that takes place where you might be alone, that takes place where there might not be cell phone reception is particularly dangerous to us. But I also want to say that I get so much enjoyment and there’s so much beauty in running and in my community that I’m not going to stop that I’m going to demand change.

What are the different challenges between running in cities and less populated areas?

The terror exists everywhere, whether it’s vigilantes or it’s the police. I can’t tell you there’s a place of safety. Every time we go outside, it’s a political act.

How often does your group encounter issues?

I mean every day, all the time, this is rooted in slavery, this is rooted in the initial social construction of race where you want the big, black man to work, but you want to make sure that he’s subdued and that he’s property because there’s a fear. When the Governor made the call that we all had to wear masks on our face everybody in our group was like, ok so now it’s a calculated risk do I go out and risk getting COVD-19---the idea of going outside and wearing a mask is problematic because the police could kill you for that and we see that. We see that in Chelsea, people are chilling, drinking Rose during a pandemic with physical distancing (requirements) and black and brown people are outside in Brooklyn getting their heads smashed to the ground.

What did you decide about the mask?

I wear a mask. Part of that is privilege too because I feel a higher level of comfort in the neighborhood that I’m in and I feel that the privilege in the way that I speak and the language that I could use and the de-escalation tactics might save my life, but that’s not always true.

Is there anything else that you’d like to add?

Allyship and support, these are active things. It’s not like you post a story and are like, "I did it.” And I don’t know everything, I’m not perfect, there’s so many blind spots that I have with so many communities that I have less interaction with and I myself must do that work and we have to pledge to continue to work on it and for folks to pledge to support people like me. This is a large task for me and anybody else to take on so when you can, support me whether it’s financially, whether it’s simply by checking in on me, whether it’s by amplifying my voice. For me to be in front of this audience is huge. I could never have imagined talking about this on your platform so thank you for that.