Salwa Eid Naser Avoids Whereabouts Ban Due To Apartment Snafu

Salwa Eid Naser Avoids Whereabouts Ban Due To Apartment Snafu

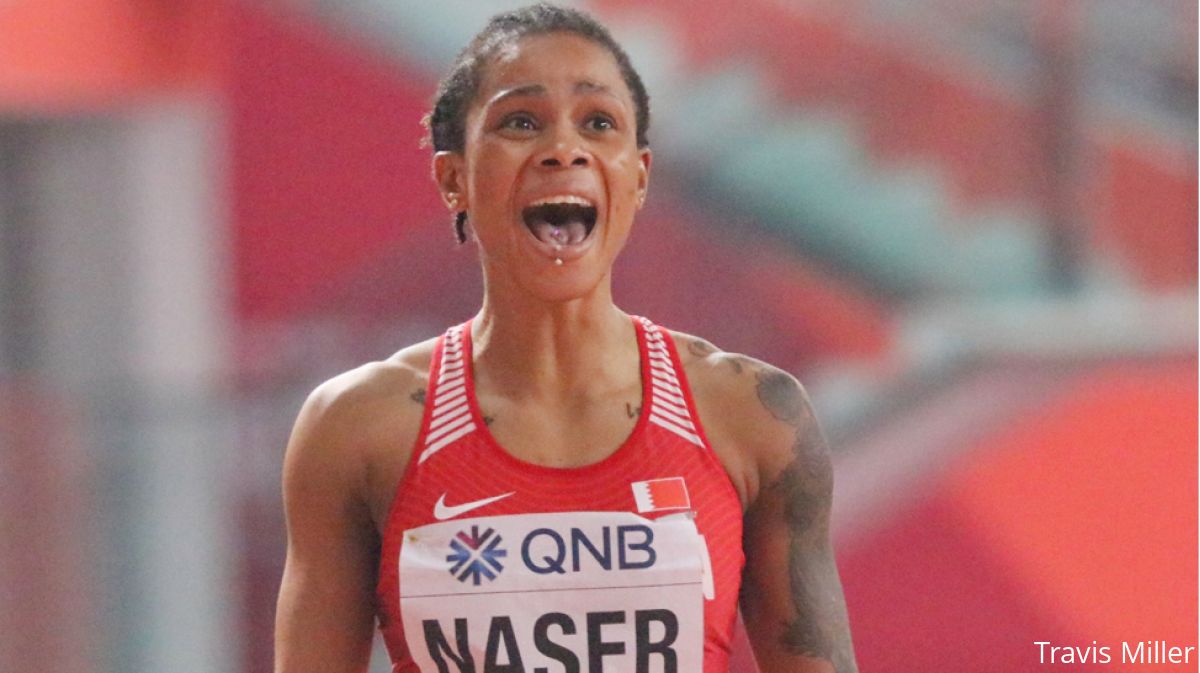

400m world champion Salwa Eid Naser will not serve a ban for whereabouts failures in a bizarre case surrounding her apartment complex.

The whereabouts case brought by the Athletics Integrity Unit (AIU) against 400m world champion Salwa Eid Naser of Bahrain has been dropped by the World Athletics Disciplinary Tribunal after a filing failure was backdated and a missed test reversed, allowing the sprinter to avoid three whereabouts failures within a 12-month period.

The World Athletics Disciplinary Tribunal has dismissed the charges brought by the AIU against Salwa Eid Naser (BRN) for alleged Whereabouts failures.

— Athletics Integrity Unit (@aiu_athletics) October 20, 2020

The decision can be read here ⬇️https://t.co/cBkQOqSHT4

Thread 👇

1/5 pic.twitter.com/u9iZOKv8cY

The 22-year-old, who won gold in Doha last fall in running the third-fastest 400m time ever (48.14), was provisionally suspended by the AIU back in June for three missed tests and a filing failure in the period between January 1, 2019 and January 24, 2020. The violations included missed tests on March 12 and April 12 of 2019, as well as January 24, 2020, and a filing failure on March 16, 2019.

As became highly publicized in the Christian Coleman case from 2019, Naser’s March 16 filing failure was backdated to the first day of the quarter, January 1, 2019 in this case, which cut down her violations within a one year span from four to three. However illogical, the quarterly method is stated plainly in the World Athletics Anti-Doping rules and was to be expected. But Naser still had the three missed tests to worry about and may have been sanctioned for them if not for a strange occurrence at her apartment complex in Bahrain in April of 2019.

The AIU release relays a “comical” (their words, not mine) story of misfortune and miscommunication from April 12, 2019 in which a doping control officer was unable to make contact with Naser to test the athlete due to a poorly labeled storage unit, a supposedly locked door and no phone number provided by the sprinter.

Naser’s listed address in the database (ADAMS) was for building 964, for which there was no actual structure. The correct location was building 954, which thankfully the DCO (a Mr. Enrique Martinez) was able to deduce due to a photo from a previous tester.

When Martinez cleared that hurdle and arrived at the correct address, he attempted to contact Naser in her unit at Flat 11. The tester located a set of doors which bore the 954 address on its side and knocked on the left side door that seemed to be associated with the number 11. But the 11 marker was not in fact associated with an apartment but instead a parking space and the door he knocked on was actually a storage unit. The release states that a number of gas canisters are “immediately visible” above the storage unit door, which is amusing when you learn that Martinez banged on that door every five minutes for an hour thinking he was at Naser’s residence.

The actual entrance to Naser’s building was at the double doors to the right of the storage unit. An intercom system was next to the door, but being that it was 6am the tester did not attempt to use it as to avoid waking other residents. The intercom didn’t work in any case, so its presence was inconsequential. The DCO tried to enter the double door, which he claimed was locked but Naser said is always left open due to the busted intercom. However, since Martinez didn’t mention the right hand door at all in his report, the tribunal sided with Naser on that point.

The DCO was still determined to contact Naser, as he then attempted to phone the world champion. Although she didn’t have a number listed in the database, Martinez dialed up a previous phone number that the testing company had on hand. That phone was disconnected.

Through all that, however, the tribunal sided with Naser as they ruled that Martinez should have opened the door on the right side to enter the 954 building and then knock on Flat 11. Case closed, Naser is free to compete.

This case seems to highlight a hole in the rulebook regarding athlete responsibility related to their upkeep of the ADAMS database. The ruling mentions that Naser “did not help herself in many regards” as she didn’t provide specific instructions for how to locate her unit and did not have a phone number listed. However, neither of these omissions constitute a violation so Naser was not held responsible for being difficult to contact. Therefore, since Martinez knocked on the wrong door-- a problem which could have easily been remedied by Naser-- the sprinter was not at fault.