How MIT Became An NCAA Division III Cross Country Powerhouse

How MIT Became An NCAA Division III Cross Country Powerhouse

How do you build a cross country team at one of the world's most prestigious universities? Under Riley Macon, MIT has aimed for solutions.

Riley Macon often has trouble keeping track of all the inquiries. Each year, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology's distance and cross country coach receives dozens of emails from high schoolers interested in joining the team and attending the school.

Who can blame them? MIT has a top-tier NCAA Division III program. More than that, it is a world-renowned university that's second in the U.S. News & World Report's most recent rankings of U.S. colleges.

It is considered the top college anywhere for people who want to pursue a career in the science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) disciplines. Macon understands he's in a fortunate position -- in that he doesn't really have to sell anyone on the merits of an MIT degree.

The hard part, though, is getting kids admitted.

Macon says MIT doesn't give much preferential treatment, if any, to athletes. He doesn't know who will be attending until the admissions department makes its decisions in mid-December for those who apply early action and mid-March for those who apply regular action.

Despite that uncertainty, MIT has been able to field competitive teams on a national level for the past 15 years. That success began under Halston Taylor, who was head coach from 2007 to 2020, and then continued with Macon, who is now in his third year.

On Nov. 18, the men's program finished eighth at the NCAA Division III cross country championships, while the women were 11th.

All of the athletes on both rosters have made it through a grueling process just to attend the school. Most MIT students have a score of at least 780 (out of 800) on the SAT math section and/or scores of at least 35 (out of 36) on the ACT math and science sections. They almost always have straight As in high school, too, according to Macon.

"Even if you have all that, you could be perfect on everything and still not get admitted," Macon said. "What MIT is trying to do is they're not trying to admit one particular type of student or one particular person. They're trying to admit a class that's very diverse from each other or within itself. It's hard to tell exactly who's going to get in and who's not."

Macon admits it's sometimes difficult when talking to recruits or their parents who want to gauge their chances of getting admitted. Prospective athletes every year choose to pursue other schools where they know they can attend by early in their senior year of high school.

Still, the pros outweigh any potential cons.

"The upside from the coaching perspective, as much as I wish I could give anyone any sort of guarantee, it's we tend to have recruiting classes and bring in people on our team that are not risk averse," Macon said. "They took the risk of applying to MIT, where there's no guarantee. It's like, they're going to take chances for what they want. That, I think, is a huge benefit athletically. In a race, sort of betting on yourself is a very important attribute. It's hard to get in, it's hard to get recruits to take the chance, but for those that do, it's a great fit."

Macon views his ending up at MIT as a fortuitous situation. After graduating from the University of Minnesota in 2016, he moved to Boston to be near his girlfriend (now wife), Whitney, who was a top runner at Harvard and New Mexico and who now runs professionally for ZAP Endurance.

Macon enrolled in a graduate program at Northeastern University and ran indoor and outdoor track for the school because he had eligibility remaining.

In the fall of 2018, Macon was a volunteer assistant at MIT before moving to earn his master's degree in exercise science at Middle Tennessee State University. Two years later, Macon received a call from Taylor, his former boss at MIT, who was retiring and wanted to see if Macon could take over in an interim capacity.

It didn't take much to convince him to move back to Boston even though it was in the middle of the COVID pandemic and the school wasn't even competing in sports. He knew Taylor had done a great job at MIT, leading the men's team to eight NCAA appearances since 2010 and the women's team to 12 consecutive NCAA meets. It was a natural fit.

Macon says he was diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder as a child, so his parents "needed somewhere to put my energy" and encouraged him to run starting in the third grade.

"I fell in love with the sport very, very early," Macon said. "I wanted to be a teacher at a young age and then once I learned, oh, hey, you can be a teacher for the sport, I was like, Man, that's kind of the exact path I want to go. Honestly, I've wanted to coach since I was in eighth grade. Some guidance counselor was asking what I wanted to do, and that's what I wanted to do."

Macon has proven to be a top-notch coach, although that's not all he does at MIT. He is also a physical education and wellness instructor at the school. He primarily teaches swimming because the school requires all students to pass a swimming test or take a swim class to graduate.

"I like teaching swimming a lot because it's an incredible life skill," Macon said. "I get to interact with an entirely different population of people that I interact with on a normal basis. And it helps me also learn that even when I'm talking to my own runners who might have a bit more experience in their activities than the swimmers I talk to, it's helpful to learn how to teach the basics well. Even if it's a different activity, swimming versus running, and it takes time and it takes energy, it can be a big asset."

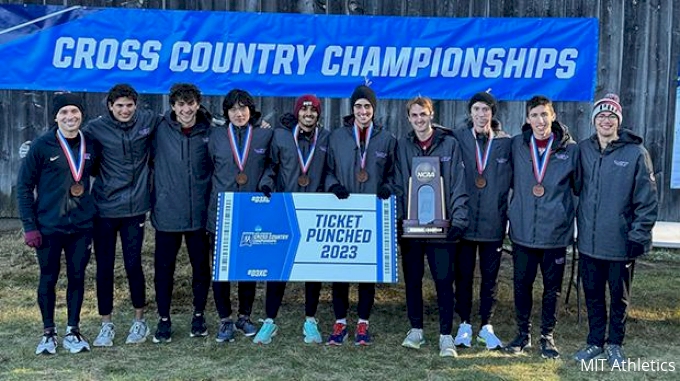

Under Macon's tutelage, MIT has continued and even exceeded the success it had with Taylor at the helm. During the fall of 2021, the MIT men finished second at the NCAA Championships (the best in school history), while the women were 12th. Macon was hired full-time last year and led the men to the national title and the women to a seventh-place finish at the NCAAs.

"What MIT is trying to do is they're not trying to admit one particular type of student or one particular person. They're trying to admit a class that's very diverse from each other or within itself. It's hard to tell exactly who's going to get in and who's not."

This year, the men and women each won the New England Women's and Men's Athletic Conference and NCAA East Regional titles.

Besides the conference and regional championships, the MIT men were also first at the Pre-National Meet at Big Spring High School. None of the three teams ranked above MIT (No. 1 UW-La Crosse, No. 2 North Central and No. 3 Carnegie Mellon) were in that field.

While the men's team is filled with upperclassmen, the women are much younger. Christina Crow, a junior electrical engineering and computer science major, is the only MIT woman who raced at last year's NCAA meet, where she finished 98th.

At the NCAA East Regional, Crow was fifth overall and third on the team behind two sophomores: Lexi Fernandez, a bioengineering major, was second overall, while Kate Sanderson, a computer science and molecular biology major, was fourth.

Macon saw the NCAA Championships as an opportunity for the young team to gain experience.

"We're blessed at MIT with the name recognition -- we can get some talented runners," Macon said. "In a lot of ways, the younger women on this team are really well equipped to handle the ins and outs of the season, manage the stresses that go on with good days and bad days."

Related Links:

- Xai Ricks, top five recruit, picks Georgia on signing day

- Behind Ella McRitchie's Quick Rise In The Pole Vault

- Allison On Her College Decision: 'I Need To Choose Oregon.'

- Notre Dame continues to land top-rated distance recruits

- The time has come for Avery Lewis to determine her future

- Mia Brahe-Pedersen has narrowed her choices down to five schools

- Adaejah Hodge, Michelle Smith navigate the recruiting process

- Iowa Gets Commitment From One Of The Nation's Top Throwers

- Rachel Forsyth's Strength Has Been On Full Display

- True NCAA men who have excelled in NCAA meets thus far

- True NCAA women who have excelled in NCAA meets thus far

- Three top NCAA programs and their XC commits

- Jason Vigilante tabbed as Princeton's new head coach

- These six schools could win big with Christian Miller's pledge

- Brayden Platt has aspirations to go two ways in track, football

- 5 True Freshmen Men Who Can Make Immediate Impact In The NCAA

- 5 True Freshmen Women Who Can Make Immediate Impact In The NCAA

- Can Joe Franklin build a track powerhouse at Louisville?

- Michigan gains pledge from high-potential miler Marcus Reilly

- Five Emerging Male Athletes From The AAU Junior Olympic Games