Unsung Heroes: Third, Fourth, and Fifth Runners

Unsung Heroes: Third, Fourth, and Fifth Runners

By: Scott Olberding

Mo Ahmed. Girma Mecheso. Brett Vaughn. Simon Bairu. All share the unique distinction of leading their respective teams to an NCAA Cross Country title. Sure, everyone gets fired up over the individual champion, and rightfully so. They’re in the lead pack, strategizing, and ultimately pull away, cementing their space in history. It’s a wonderful feeling I’ve been told. Plus you’d be first in line for the banana and water table, which is nice.

But what I’m here to tell you, which I’ve debated to great lengths about with equally nerdy cross country enthusiasts, is this: Your first two runners don’t matter. That’s right I said it. I’m sick of the Chris Derricks, the Andrew Ledwiths, the Colby Lowes, and the Tom Farrells getting all the attention. They don’t matter.

To be fair, I should clarify. Clearly your top two runners make a difference. Intrinsically, you need them to be your first and second scorers; if not for them, you would be scoring your 6th and 7th runners and as a former 6th man, I can attest that nobody wants this. Furthermore, if your top two athletes are really good, you’re basically only scoring three people. But what I’m hear to suggest, and hopefully prove, is specifically that how your third, forth, and fifth runners perform on race day is much more important than your first and second. To be even clearer, the first and second runners of a championship-seeking caliber team have a much larger margin of error than runners 3-5.

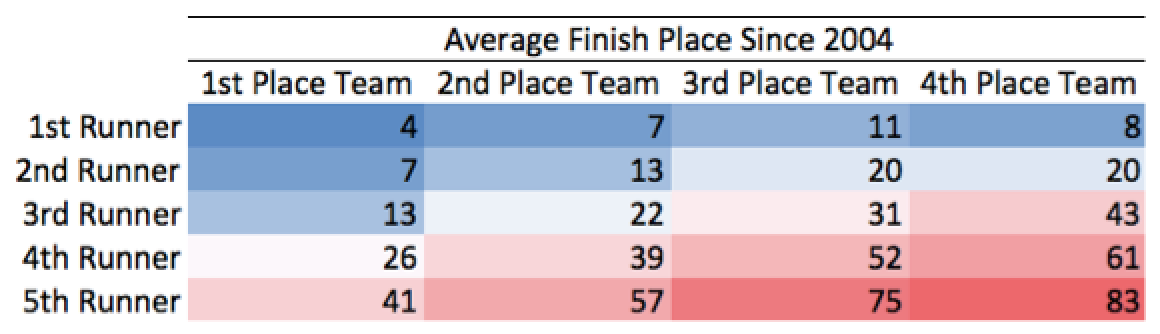

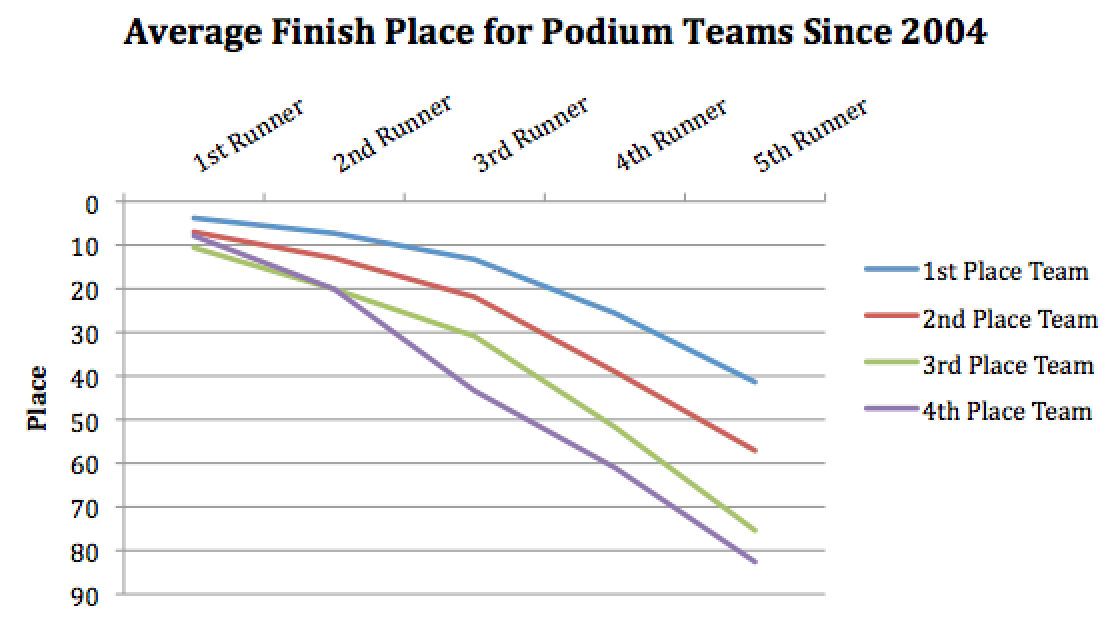

In order to demonstrate this idea, I’ve aggregated the team scoring results for the top four men’s teams dating back to 2004 (10 years). Below is the average finish position for each runner for all podium teams.

To visually differentiate the make-up of placement of each average finish, I’ve added conditional formatting to the above table, with blue representing a low finish score and red representing a high score. As indicated by the above gradient, on a relative scale, the first two runners for all four teams don’t make a significant difference; they are all a pleasant hue of blue. The placement of third, fourth, and fifth runners is where championship teams are made.

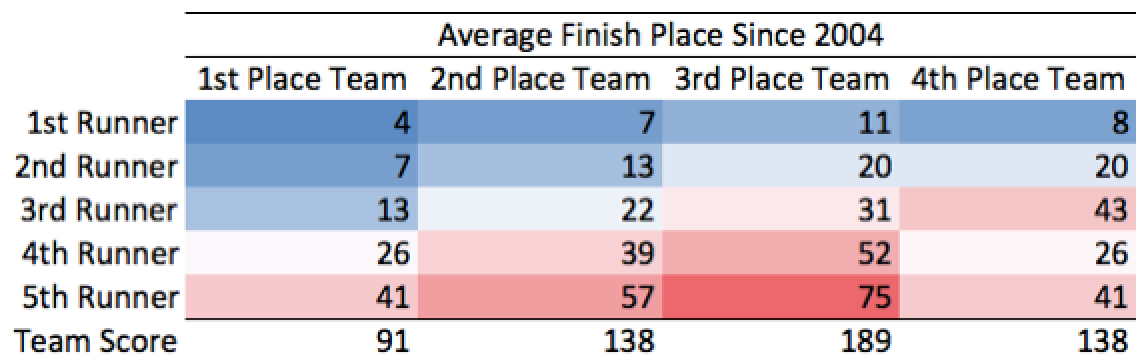

In fact, if our “average” fourth place team replaced their bottom two runners with the 4th and 5th runners of the top team, the former 4th place team would essentially be in a dead-heat for second place.

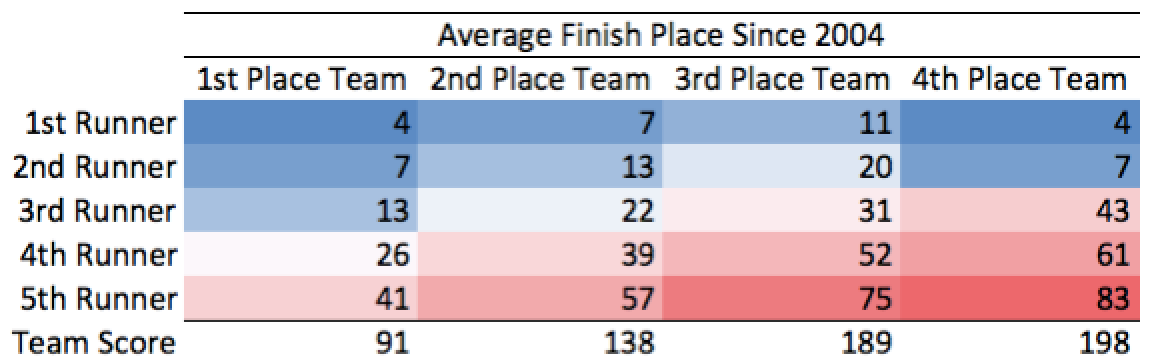

Alternatively, swapping runners one and two from the first place team to the fourth place team has virtually no effect. This “upgraded” fourth place team only scores 17 fewer points when trading their first two scorers for runners one and two from the first place team.

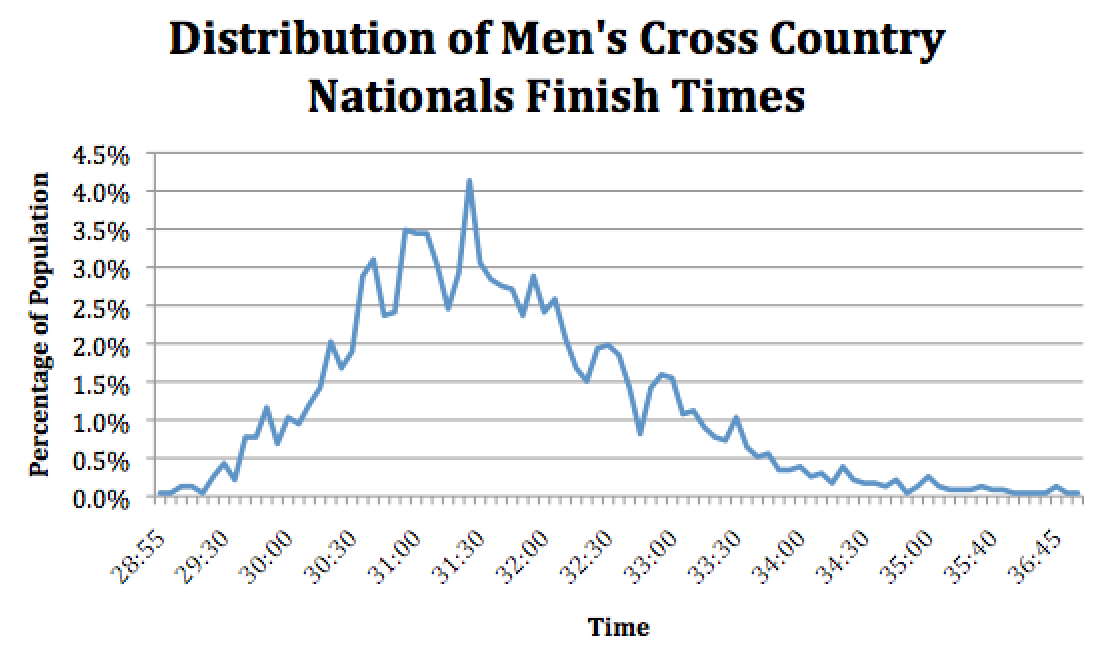

This all lends to the idea that the top few runners per team have a much larger margin of error when racing, as opposed to runners three, four and five. This is almost entirely due to the distribution of runners within a race. Below is a graphical representation of the past ten Men’s National Championships, with times rounded to the nearest five-second interval.

To further illustrate the dispersion between each place, the graphic below shows the spread of each hypothetical runner across our aggregate teams.

It isn’t that the difference between the fourth place team’s fourth runner and the first place team’s fourth runner is wildly different; they are just battling WAY more athletes for their position. If I woke up in NAU Head Coach Eric Heins’s body and was given one wish from the omnipotent magic cross country genie, I would much rather swap Northern Arizona’s Josh Hardin and Nathan Weitz For Colorado’s Pierce Murphy and Ammar Moussa than Futsum Zienasellassie and Matt McElroy for Ben Saarel and Morgan Pearson.

Like Cassius mused in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, “The fault dear Brutus, lies not in our stars, but in ourselves.” Or more aptly framed for cross country, the fault lies in the linear nature of scoring across a normal distribution and our third, fourth, and fifth runners.

Follow Scott @isthatsol