The Inaugural Women's Decathlon Championship Is A Big Deal And Here's Why

The Inaugural Women's Decathlon Championship Is A Big Deal And Here's Why

The first women's open decathlon championship in the modern era of USATF will be held this summer in what is a groundbreaking moment for the sport.

The modern era of track and field has nearly equalized opportunities at the sport’s highest levels for male and female athletes, with one key outlier: the combined events.

Although men have competed across 10 events in various forms of the decathlon since the 1890s, women are still limited to the seven-event heptathlon at the World Championships and Olympics.

But this summer, one week after the USATF Outdoor Track & Field Championships, history will quietly unfold as the first Women’s Open Decathlon Championship in the modern era of USATF takes place in Grass Valley, California.

Prize money to the tune of $500, $200 and $100 for the top three athletes will be provided by Pole Vault Power, and the event will be held in conjunction with the previously existing USATF Masters Combined Events Championship as a cost-saving measure.

You can find out more about the women’s open decathlon championship and sign up to compete here.

The women’s decathlon has been of special interest for the event’s athlete coordinator, Becca Peter—the woman behind Pole Vault Power—since 2000, when she was a senior in high school.

“I wanted to do decathlon when I was in high school, but girls pole vault was brand new,” she said. “Senior year was the first year we had pole vault in our state. ‘Decathlon is the next thing,’ I thought at the time. ‘It’s not here yet, but it’ll be here soon.’”

Seventeen years later, the women’s decathlon has yet to arrive. While the IAAF ratified the women’s decathlon as an official event in January of 2005, there have been few competitive opportunities.

The world record has stood at 8,366 points since April of that year, when Lithuanian heptathlete and two-time Olympic medalist Austra Skujyte beat the previous record by 206 points at the Audrey Walton Combined Events meet hosted by the University of Missouri.

Skujyte, a two-time NCAA heptathlon champion for Kansas State, would win the women’s decathlon at Audrey Walton again in 2006, ahead of college teammate Breanna Eveland, who set the first and only ratified American record of 7,064 points.

But the Audrey Walton Combined Events meet was short-lived. A year later, Missouri switched out the only high performance women’s decathlon in North America for the heptathlon, and discontinued the meet entirely soon after.

What had seemed like a sure thing when women’s pole vault was added to the Olympic program in 2000, became, at the elite level, non-existent.

Stacy Dragila: “The Heptathlon Is Too Easy”

Stacy Dragila celebrates winning gold at the inaugural women's Olympic pole vault competition at the 2000 Sydney Games. Courtesy of Photo Run.

Stacy Dragila, who won the first-ever Olympic gold medal in the women’s pole vault in 2000, is perplexed that the decathlon still isn’t a standard event for women.

“I think the heptathlon is really too easy for elite women,” Dragila said over the phone from her home in Boise, Idaho, where she coaches youth pole vaulters. “We should throw in another event to make it more technical. Now that the pole vault has been contested for so long—18 years—why not give women an opportunity to try it?”

When you compare the lineup of events in the decathlon to the heptathlon, it’s clear which event requires the more unique skill set.

| DECATHLON | HEPTATHLON |

| 100m | 200m |

| long jump | long jump |

| shot put | shot put |

| high jump | high jump |

| 400m | X |

| 110m hurdles | 100m hurdles |

| discus | X |

| pole vault | X |

| javelin | javelin |

| 1500m | 800m |

“You find someone who’s fast and powerful, they dominate the hep,” Dragila said. “I think there just needs to be another technical event in there to set the field apart. There’s not enough differentiation in technique. [Pole vault is] pretty grueling if you don’t put time into it, and there are women who are against it because it just takes that much more time to train, but if the men are doing it, why can’t the women do it?”

Dragila has a unique perspective on the women’s combined events—after all, the three-time pole vault world champion started her track career as a heptathlete.

Her coach at Idaho State, Dave Nielsen—who now coaches at Eastern Washington—was a big proponent of encouraging his female athletes to test out the pole vault, hammer throw and weight throw before they were official NCAA events for women.

Dragila said Nielsen would “bribe” her and a few other heptathletes to dedicate a portion of afternoon practice to the pole vault and to compete in pole vault exhibitions before their home meets as other teams trickled into the stadium. If they did, he released them from a more strenuous part of their workout.

“‘The four of you heptathletes, you’re gonna come in 30 minutes before the rest of the teams and you’re gonna be jumping,’” Dragila remembers her coach saying. “‘Hopefully, by you being on the runway, other girls and coaches are gonna be excited about it.’”

Despite Dragila’s assertions that she “wasn’t awesome at it at first,” she soon set her first of many American records in 1994 with a clearance of 3.05m/10 feet. She would win 17 U.S. titles, break the world record multiple times in her career, and set a lifetime best of 4.83m/15-8.

Stacy Dragila's gold medal-winning clearance at the 2000 Sydney Olympic Games. Courtesy of Photo Run.

When Dragila returned to the United States after winning her first world title at the 1997 IAAF World Indoor Championships—the first time the women’s pole vault was contested at a global championship—she competed in her first, and only, decathlon.

“Coach said, ‘Hey, when you get back from Worlds, we need to do the decathlon. We need to start this now. With the women’s pole vault doing well, this is when we have to push for it,’” Dragila remembers Nielsen telling her. “I thought, ‘I’m gonna do a decathlon? I have to run a 1500?!’

“That’s what I was stressed about! So I just took it in stride; had a lot of fun doing it. It came down to that 1500m, and I got locked up and didn’t know where I was on the track, but I posted a time!”

At the time, Dragila’s 6,999-point score was the best total ever for an American woman, and vastly improved on Jenny Stary’s previous U.S. best of 6,027 points from 1980 (scores adjusted to current point tables).

But neither record was ever ratified, as the event was not yet recognized by USATF.

The women’s decathlon never caught the general public’s attention the way pole vault had.

“Since then… people would get excited about it, then put it on the back burner; people would bring it up, and it would get shot down again,” Dragila said of the women’s decathlon.

The First Female Decathletes

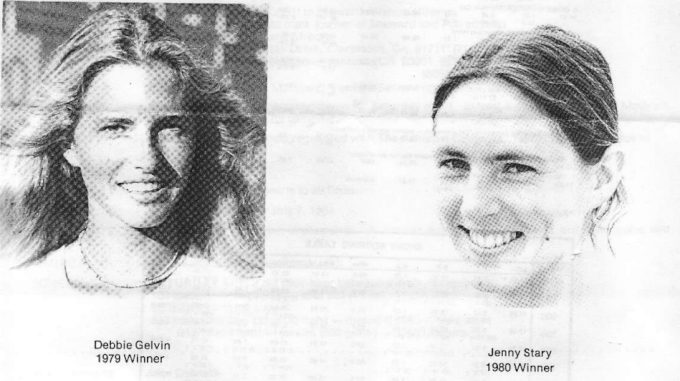

In the late 1970s and early 80s, four women’s decathlons were hosted in Ventura, California by The Athletics Congress (TAC), which governed the sport of track and field in the United States before rebranding as USATF in 1992.

TAC Era Women’s Decathlon Champions (Scores adjusted to modern point tables)

| YEAR | 1979 | 1980 | 1981 | 1982 |

| NAME | Debbie Gelvin | Jenny Stary | Linda Hightower | Sharon Hanson |

| SCORE | 5116 | 6556 | 5989 | 6198 |

| 100M | 13.27 | 13.72 | 12.82 | 12.9 |

| LJ | 4.54m/14-10.75 | 5.31m/17-5 | 5.08m/16-8 | 5.02m/16-5.5 |

| SP | 7.54m/24-9 | 12.22m/40-1.25 | 7.44m/24-5 | 10.08m/33-1 |

| HJ | 1.52m/4-11.75 | 1.59m/5-2.5 | 1.71m/5-7.5 | 1.39m/4-6.75 |

| 400M | 64.22 | 61.56 | 57.78 | 61.7 |

| 100H | 16.32 | 17 | 15.19 | 15.1 |

| DISCUS | 17.20m/56-5 | 37.38m/122-8 | 28.22m/92-7 | 29.90m/98-1 |

| PV | 2.05m/6-8.75 | 2.47m/8-1.25 | NH | 2.22m/7-3.25 |

| JT | 22.90m/75-1 | 34.82m/114-3 | 30.66m/100-7 | 35.24m/115-7 |

| 1500M | 6:03.6 | 5:44.55 | 5:24.21 | 5:47.2 |

Of the TAC-era decathlon champions, only Hanson has much of a place in history. The Lake Charles, Louisiana, native made the Olympic heptathlon team in 1996, and placed ninth in Atlanta.

Louise Tricard’s definitive, two-part volume, “American Women’s Track & Field: A History,” refers only to the 1982 event.

“There were three previous meets, but this one was officially designated the National Women’s Decathlon Championships,” she wrote. “These decathlon meets may be the first women’s decathlon competitions in the United States.”

And pretty much the last, until this year.

The factor that seemed to hold women back from the decathlon throughout history was widespread doubt that females could successfully and safely pole vault.

But even though Dragila’s trailblazing days weren’t until the late 1990s, women have actually competed in the pole vault since the early days of sport.

The very first women’s track and field competition, then called a “field day,” was held at Vassar College in 1895, and featured five events: the 100-yard dash, 220-yard dash, running broad jump, 120-yard hurdles and high jump.

The following year saw the introduction of the “fence vault,” which may be an early precursor to the pole vault, as subsequent records began referring to the pole vault in place of the fence vault beginning in 1911, when Spalding’s Official Athletic Almanac credits Ruth Spencer of Lake Erie College with setting the women’s record at 5-8.

Women’s pole vault later became somewhat of a sacrificial lamb to allow for the general rise of women in athletics.

Dr. Harry Eaton Stewart, an influential medical doctor in the early 1900s, is credited in Tricard’s texts with challenging and ultimately changing the prevailing cultural attitude that competition and physical exertion were inherently bad for women through his frequent articles in the American Physical Education Review.

Still, he also advised that “only the exceptional girl was to pole vault, run the 220, or put the 12-pound shot.”

The first meeting of the National Women’s Track and Field Committee in 1918 followed Stewart’s recommendation to drop the pole vault from its standard event list, along with other events thought to be “dangerous”: the 100-yard hurdles, 200-yard run, and 12-pound shot put.

In 1922, the various groups involved in organizing women’s track and field were folded into the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) and decades of extreme restrictions on the participation of women in the sport commenced.

“A majority male vote” saw the committee reject a proposal to add the women’s pole vault back to the standard program in 1925.

Women competed in the short hurdles over various distances at the Olympics starting in 1932, and the women’s 200m and shot put were added to the Olympics in 1948.

But the pole vault would remain in limbo for another five decades.

What About The Heptathletes?

Nafissatou Thiam of Belgium is the reigning world and Olympic champion in the heptathlon. © Christopher Hanewinckel-USA TODAY Sports.

“Why do women do the hep and not the dec?” Peter asks. “One hundred percent, that’s rooted in misogyny. It comes from decades of belief that it is bad for women to exert themselves.

“But that doesn’t mean that women who do the hep today are promoting misogyny. The heptathlon has created its own history and there is a lot of concern that if we did replace it with the decathlon, that history would be forgotten.”

It’s certainly difficult to see a future in the sport for two separate women’s combined events.

The women’s outdoor heptathlon as we know it today was a replacement for the pentathlon—which is still contested indoors—in the 1980s. But the jump from pentathlon to heptathlon was much more complementary to combined events athletes’ pre-existing skill sets, as the only added events were the 200m and the javelin.

“It took decades to make events like triple jump and pole vault available to women, but in the end, all they had to do was add an event,” Peter said. “They did not have to displace an existing event.”

“The decathlon is threatening to a lot of heptathletes. There are some who would like to try it, but generally, most elite heptathletes seem to be opposed to the concept of women doing the decathlon because they recognize that if the decathlon gets a foothold, it could threaten their careers. That’s a perfectly understandable place to argue from.”

FloTrack asked U.S. combined events star Kendall Williams about her thoughts on the decathlon at this March’s IAAF World Indoor Championships. Watch the video interview below.

“Oh man, I would like to see it,” Williams said after taking ninth in the world indoor pentathlon final. “I don’t know if I would participate. Only after my time is done! I will cheer for the female decathletes.

“Only because of the pole vault. That’s the scary thing, we would have to learn technique for the vault and the discus, and I think that would be… it would be interesting. I watched my brother do [pole vault] and I felt scared for him. I know some heptathletes are fired up for it to turn into a decathlon one day, so we’ll see.”

For Peter, the goal isn’t necessarily to get women’s decathlon in the World Championships or the Olympics.

“In the future, I am hoping we can contest this decathlon later in the summer, which would allow interested heptathletes to also give it a try,” she said. “It could be a fun opportunity for younger heptathletes to gain experience and earn prize money. We cannot even begin to have the conversation about which event to contest at the international level until we have solid domestic opportunities.”

For Dragila, the issue of the women’s combined events cuts close to home with her experience as a pioneer in the women’s pole vault.

“Women wanted to pole vault for so long, but so many people in our sport—especially men—just didn’t think we had to upper body strength to do it. They didn’t think women could jump very high. From the beginning, I was told, ‘So what if you’re pole vaulting? No one’s gonna watch you.’ I’m so glad for those people tripping in my ear and telling me all these negative things because it really spurred me to get better.

“Don’t tell us women we can’t do something. I think it’s just time that women have the opportunity to test our limits in sport. It takes so much bravery to get out there and do such a long, grueling event.”