What Happened To The Sub-13:00 5k?

What Happened To The Sub-13:00 5k?

The men's 5k is experiencing a slump the likes of which haven't been seen in 25 years. But why?

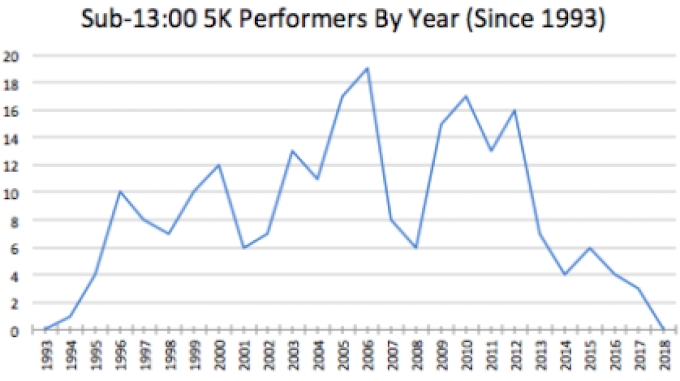

The last time that the world failed to produce a single sub-13:00 5,000m performance in a calendar year, not one of the current 10 fastest athletes in the event was even born yet. Not since 1993 has the 13:00 barrier failed to get broken by at least one athlete, an unfortunate fate that 2018’s top 5k runners might soon share with those men from 25 years ago.

With the Brussels Diamond League final on August 31 marking the IAAF’s last prominent male 5,000m race of the 2018 season, a failure by the field to go sub-13:00 in Belgium will likely seal that fate. And with the IAAF Diamond League title and a $50,000 winning prize on the line in a winner-take-all final in Brussels, there’s a good chance that the race will be run like a tactical championship 5k. Translation: probably no sub-13:00 times this year.

So how did we get here? How did an event that produced 16 sub-13:00 performances as recently as 2012 arrive on the cusp of distance running infamy six years later?

To start, let’s look at the top-12 athletes in the current Diamond League 5k standings (12 qualify for the Brussels final) to get a gauge of who has made the most noise in the event in 2018 and how they’ve done it.

The 5k Class of 2018

Athlete (Country) | SB | PB | # of Sub-13 (Career) | # of 5k in 2018 |

Birhanu Balew (BRN) | 13:01.09 | 13:01.09 | 0 | 4 |

Selemon Barega (ETH) | 13:02.67 | 12:55.58 | 1 | 5 |

Muktar Edris (ETH) | 13:06.24 | 12:54.83 | 4 | 3 |

Yomif Kejelcha (ETH) | 13:14.39 | 12:53.98 | 2 | 1 |

Paul Chelimo (USA) | 13:09.66 | 13:03.90 | 0 | 3 |

Abadi Hadis (ETH) | 13:03.62 | 13:02.49 | 0 | 3 |

Mo Ahmed (CAN) | 13:14.88 | 13:01.74 | 0 | 4 |

Hagos Gebrhiwet (ETH) | 13:16.39 | 12:47.53 | 6 | 1 |

Stewart McSweyn (AUS) | 13:19.96 | 13:19.96 | 0 | 4 |

Getaneh Molla (ETH) | 13:04.04 | 13:04.04 | 0 | 3 |

Richard Yator (KEN) | 13:04.97 | 13:04.97 | 0 | 6 |

Ben True (USA) | 13:16.48 | 13:02.74 | 0 | 2 |

Only four of the men who have qualified for this year’s Diamond League final have ever broken 13:00, and of those four, just two-- Barega and Edris-- have dipped under the barrier since the start of 2017.

The talent crop for the 5,000m was already a bit watered down entering the season, but with Gebrhiwet and Kejelcha-- the two fastest men listed above by PB-- having finished just one outdoor 5k each so far this season (Kejelcha was DQ’d in Lausanne), the chances of a sub-13:00 performance have been hit even harder in 2018. With so few men on the circuit right now having ever run that fast, and just two who own sub-13:00 PBs having completed more than one 5k so far this season, you have the recipe for our current predicament.

It should also be noted how much talent the 5,000m has lost in the recent years. Here’s a look at the sub-13:00 performers over the previous three seasons who have either scarcely raced 5,000m this season, or have not competed in the distance at all this year, for a variety of reasons:

The Departed Stars

Athlete | PB | # of Sub-13:00 (Career) | # of Outdoor Global Medals | # of 5k in 2018 |

Joshua Cheptegui (UGA) | 12:59.83 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Mo Farah (GBR) | 12:53.11 | 4 | 12 | 0 |

Dejen Gebremeskel (ETH) | 12:46.81 | 6 | 2 | 0 |

Abdelaati Iguider (MAR) | 12:59.25 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

Geoffrey Kamworor (KEN) | 12:59.98 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

Imane Merga (ETH) | 12:53.58 | 11 | 1 | 0 |

Paul Tanui (KEN) | 12:58.69 | 1 | 4 | 2 |

Thomas Longosiwa (KEN) | 12:49.04 | 11 | 1 | 0 |

Of course, we know Farah has retired from the track in favor of the marathon, while the 2017 NYC Marathon champ Kamworor is preparing for his title defense in November, and has also not touched the track at all this year. In total, these eight men with a combined 36 career sub-13:00 5,000m performances are either no longer active, skipped the event entirely this season, or have barely raced the distance in 2018. Their combined absence has certainly left a considerable void in an event that routinely saw sub-13:00 times in the past.

While the departures of those studs-- and the relative inexperience of the current 5k athletes-- has certainly impacted the event in the short term, the downward trend towards less and less sub-13:00s each season has been in the works for some time now.

Other than a brief uptick from four sub-13:00s in 2014 to six in 2015, the amount of such performances per season has been in steady decline since 2012. And consider that aside from a four year resurgence of sub-13:00s from 2009 to 2012 that included at least 13 athletes under the barrier each season during that time, the amount of sub-13:00s per season has hung around the single digits for the most part after reaching its high watermark of 19 in 2006.

Follow The Money

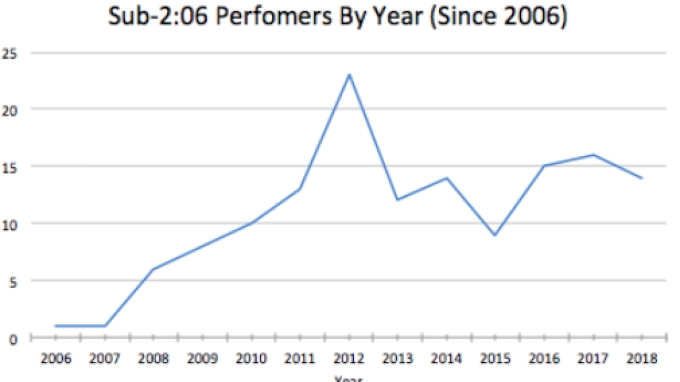

And an increased focus in the marathon, where there is more money to be made for the elite masses than on the track, is at least partially to blame here . That mostly downward trend ever since 19 men incredibly ran under 13:00 in one season in 2006 has coincided with a sharp rise in the number of sub-2:06 marathons during a similar time frame:

During the same season that the amount of sub-13:00 performers reached an all-time high in 2006, the marathon had just one sub-2:06 performance. That was the case the following season in 2007, as Ethiopian legend Haile Gebrselassie was once again the only athlete to crack 2:06.

But from there the marathon takes off just as the amount of elite 5k performances begins to fall. Not coincidentally, the Abbott World Marathon Majors-- the competition series that encompasses six big city marathons across the globe-- was founded in 2006 and dramatically increased the financial incentives for athletes to compete in the event. With a hefty $500,000 payout (now $250,000) awarded to the series champion over the span of the six races, it’s not surprising that the number of quick marathons dramatically spiked in the years following AWMM’s founding. The extra cash that suddenly became available on the roads no doubt caused many a quality 5k athlete to trade in their track spikes for racing flats earlier than they would have otherwise.

The Superstar Effect

But what about 2009 through 2012, you say, when the amount of sub-13:00 times rebounded to their pre-2007 levels? This sudden return of a bounty of speedy times during this period appears to be temporarily inflated by a factor that has not applied in 2018: the superstar effect.

In 2009, Kenenisa Bekele won three sub-13:00 5k races, leading to a combined 14 other performances under the barrier in those races. Bekele broke 13:00 a whopping 21 times over his incredible career, and there’s no doubt his aggressive racing style contributed to many other athletes going under 13:00 in the 5k, especially in 2009. That’s the superstar effect. The same goes for Mo Farah and Bernard Lagat in 2011 in Monaco, when the two legends were each duking it out for separate national records; their battle for history produced the two fastest times of the year, and led to five other guys cracking 13:00 in one race. With no legends of the magnitude of those three active right now, the 5k as is lacks a clear superstar for everyone else to chase en route to quick times.

And even without a huge name dominating up front, the 2012 count of 16 sub-13:00s was propelled by a singular scintillating race at the Paris Diamond League that produced 11 times under 13 and six under 12:50, making it the deepest 5k in history. No other race has produced as many top 20 all-time 5k performances as that one. As such, an outlier race like that can skew the numbers and suggest a trend that isn’t as strong as it appears.

There’s also the matter of doping, which is all but impossible to eliminate as a contributing factor to a number of sub-13:00 5k times over the years. Testing has supposedly improved in recent years, especially out-of-competition, but without verifiable proof that any particular era is dirtier than another, it’s difficult to quantify the impact in this context. But as the elephant in the room, doping warrants a mention here.

Other factors have likely contributed to the demise of the once routine sub-13:00 5k, but the combination of a relatively weak talent crop this season, the recent departure of former track stars, and the mass migration to the marathon for bigger pay days has certainly damaged the quality of the event both short and long term. The brief recovery that the 5k experienced from 2009 to 2012 appears to be an anomaly upon closer inspection, as the high number of sub-13:00s during those years were caused by factors that don’t apply right now.

Will the 5k rebound? We certainly haven’t seen the last sub-13:00 5k performance, but in a year without a ton depth, it’s quite possible that the 2018 5k season ends up looking a lot like its predecessor from 25 years ago.